The short story

Tartak is probably a fallen "god" or angel (IE: a demon) in the Old Testament who was worshiped by the Avites. In contrast, Christians worship the one Supreme God who is above all, above even His created angels.

Tartak is one of the idols mentioned in the second book of Kings (also called ”4th Kingdoms” in older Bibles) that were set up in Samaria by the people who were living there. 2 Kings chapter 17 describes the religious confusion that occurred in the land when the priests of the Israelites were trying to teach the people how to practice proper worship of the Lord God, but those dwelling in the lands nevertheless built a variety of idols in an attempt at piety. The text describes the various gods that they built, including Sukkoth Benoth, Nergal, Ashima, and Tartak.

What do we know about Tartak, specifically? Very little, other than Tartak was the god set up by the Avites. There has been some scholarly debate about this figure, but none of it has been very conclusive. It’s been suggested that he was a form of the Egyptian god Typho, or that he was some sort of hero of the underworld, or was perhaps related to the worship of Mars. If the name is Persian, as some believe, it might mean “intense darkness” or “hero of the underworld”, but other sources suggest it might have something to do with being “chained” or “bound” – which could be a connection to the dungeon Tartarus, a place in the Greek underworld of suffering and chains. But the exact meaning of the name is not clear.

What’s more important than figuring out the exact identity of this god is understanding the broader context of how ancient people thought about religion. Many of the things that modern people say about ancient religion ends up being misleading, so the correct context will help you get a better understanding of what’s happening in these sorts of episodes.

Monotheism vs. henotheism

One of the major misconceptions many people have about the ancient world is the idea that the ancient Israelites and early Christians were “monotheistic” – meaning that they only believed in the existence of one God – while ancient pagans (everyone else) were “polytheistic” – meaning that they believed in many gods.

The Bible acknowledges that other spiritual entities exist, and refers to them as “gods”.

However, the scriptures are also very clear that there is a particular entity that is above those gods in a very profound sense. The scriptures refer to this entity, the ”God of Israel“, as higher than the other spiritual entities, the “Lord of lords” and the “God of Gods”. The idea is that the lower gods – like Zeus or Thor or Tartak – really did exist, but there was an entity above them, so much higher than them that he was referred to as their god, the God of the gods. This idea is known as henotheism, which is the belief that, while many gods exist, there is a single, supreme, ultimate entity that is above the other gods and rules over the entire universe. This was the belief of the ancient Israelites and of the early Christians.

Does this idea take away the dignity or otherwise undermine the glory of the one God of Israel or the God who is the Father of Jesus? Not at all. The problem is that we use the same word – the word “god” – in both cases, but these two cases are entirely different. Think about it like this: when we use the word “god” with a lower-case “g”, what we’re referring to are superhuman spiritual entities. If you look at the Biblical texts, the Jewish literature written during the second temple period, and the writings of the early Christians, you’ll notice that they all have a shared understanding that the universe is full of a vast multitude of incredibly powerful spiritual beings: cherubim, seraphim, demons, angels, and a whole myriad of ancient pagan deities who are presented as being real and having real power. However, despite being superhuman, these entities are still a part of the universe and their power is, therefore, limited.

The God of gods like Tartak

On the other hand, all the great religious traditions of the ancient world realized that there had to be something higher than even the highest of the created beings. For the universe to exist and have order, there had to be some principle, power, or force that was the source of life and being and that gave order to reality. This would be something akin to “being itself”, “reality itself”, or the “principle of being”. Every great culture had a name for this power and it had many names across many languages. In ancient Greek it was called the “logos”, in Chinese it was called the “Tao”, in Hindi it was called ”Ṛta”, and so forth. They all understood the difference between the things in the created universe and that power or principle by which those things had their being.

The difference between these other cultures and the understanding of the ancient Israelites and early Christians was that this power was more than an abstract principle or a mysterious force, it was also a person – something with a mind and a will. This is the meaning behind the word “God” spelled with an upper-case “G”. When we say “God” in this sense we are referring to that mind that is the source and author of reality itself. He is a God in the sense that he is the God of the gods, infinitely more and infinitely higher than they are. They are created, limited, bound in time, and possessing of physical bodies of some kind. But the God of gods is uncreated, unlimited, timeless, ageless, spaceless, and immaterial. These two categories are so different that they are in fact opposites.

Early Christians understood this distinction very well. St. Augustine, writing in the early church period, observed that the pagans used the word “gods” to refer to the entities that Christians called “angels”. He saw no problem with these words being synonymous, as long as everyone understood the difference between the “lower” or “petty” deities that we call “gods” and the one God who is the source and author of all things.

J.R.R. Tolkien, a devout Catholic writer, makes this same distinction in his own mythology. In the creation story in his text, The Silmarillion, the God of gods is called Eru. Eru creates the Ainur, who are the “little gods”. Eru includes the Ainur in his work of creating the world. But it is always understood that these little gods are his creations as well, regardless of the superhuman, cosmic power they wield over the created world. One of these Ainur went bad and “fell”, just the way the Devil fell, and he collected a group of rebel spirits to assist him in his attempt to usurp the God of gods and take over creation for himself. But his efforts ultimately fail (and could never have succeeded) because – by his nature – he cannot overthrow Eru, his own creator.

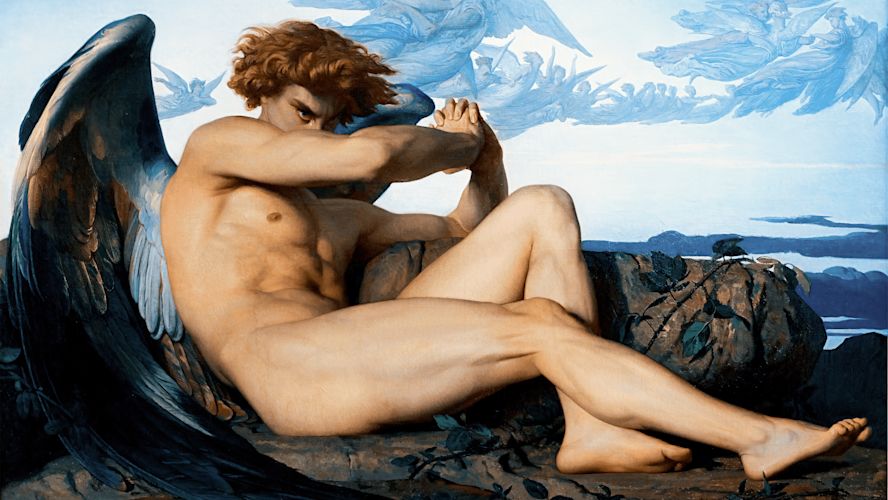

The fall of the little gods

The same story of the gods being originally appointed to steward creation but ultimately “going bad” is present in the Biblical narrative as understood by the ancient Israelites and the early Christians. Old Testament scholar Dr. Stephen de Young, in his book Religion of the Apostles, explains that the tower of Babel incident is a story about how a group of little gods ended up corrupting humanity. The effort to build a tower of Babel was an incident where human beings were attempting to create a “mountain of assembly” as a way of “drawing God down from heaven in order to manipulate and control Him” (de Young, p.70). God subsequently divides the nations into different groups based on language, so that, presumably, they are no longer able to cooperate. Most interpretations of this story emphasize the scattering of the nations as the origin of the world’s different languages, but there is a later, important passage in Deuteronomy that clarifies what happened here. Deuteronomy 32:8 reads, “When the Most High divided their inheritance to the nations, When He separated the sons of Adam, He set the boundaries of the peoples according to the number of the children of Israel”.

What does this passage mean? First, de Young clarifies that this translation, though common, is misleading. “In addition to making little to no sense in context,” he writes, “nowhere do the Scriptures number the nations at twelve. The Greek text of Deuteronomy translates an earlier form of the Hebrew, stating that God divided them ‘according to the number of his Angels.’ Recently, among the Dead Sea Scrolls, the original Hebrew wording has been recovered, which indicates that they had been divided ‘according to the number of the sons of God’” (de Young, p.70). In other words, when God scattered the nations after the tower of Babel, he divided up the nations according to the angelic powers – the "gods". He put these fledgling nations under the supervision of these local gods.

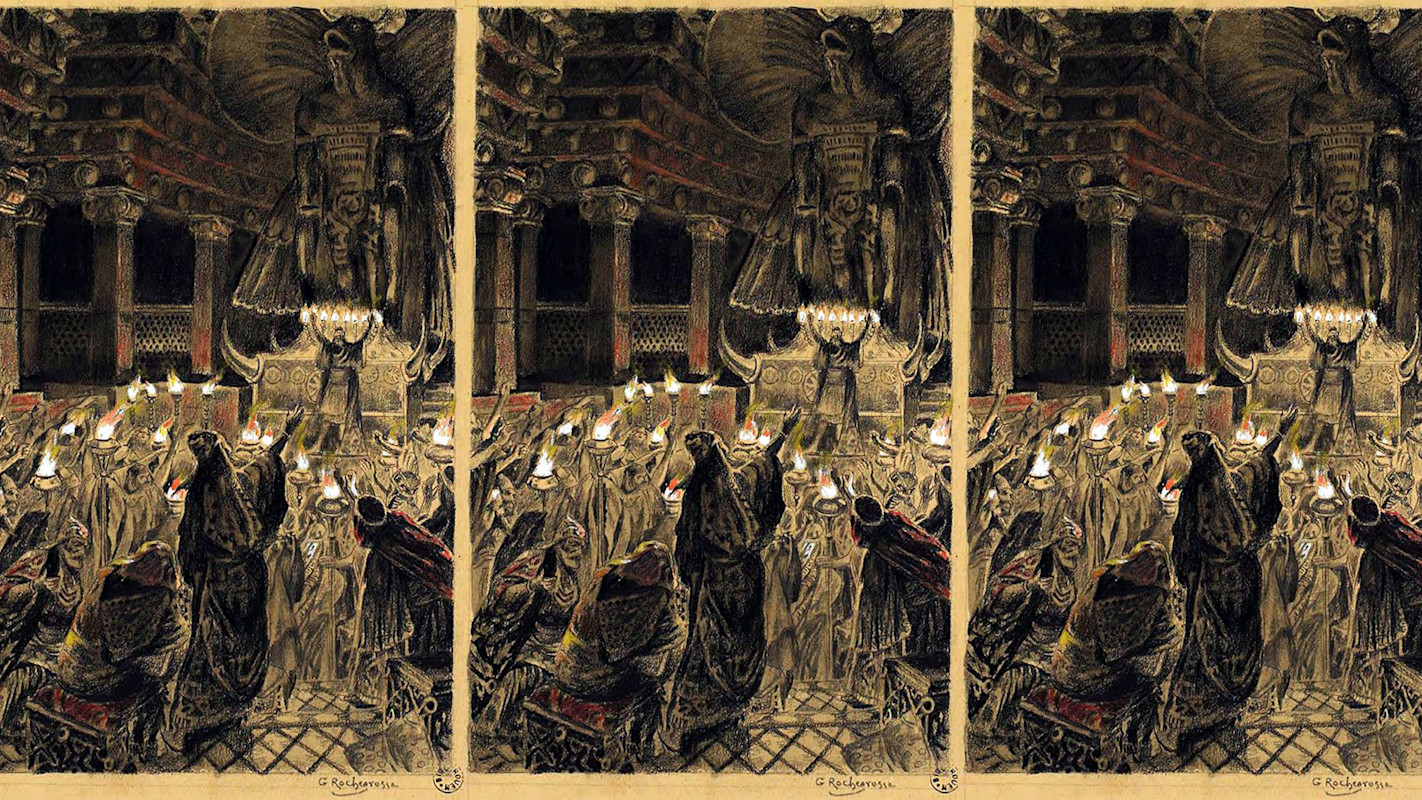

Foster Bible Pictures - Sacrificing a child to Molech - 1897

The problem is that these angels became corrupt and desired worship from the people they were supposed to steward. This, according to the early church fathers, is what gives birth to all of the pagan religions. And throughout the Bible there is a constant identification of “gods of the nations” with demons – in other words, fallen angels or, you might say, corrupt gods (Deut. 32:17, Ps. 96/95:5; 1 Cor 10:20).

So what can we say about Tartak?

Most likely he (or it) was a real creature, one of those spiritual creatures that was supposed to guard and steward the nations, but became corrupt. Ancient people built idols in order to interact with and please these gods, so that they could offer sacrifice to them and perhaps receive their blessings and aid. But if these creatures were corrupt, then worshiping them and asking for their help would be to follow them down their dark path of corruption and evil.

And this is exactly what we see in this biblical passage. The text mentions how the religious practices these people performed were morally abhorrent, specifically listing child sacrifice among them. Indeed, child sacrifice is mentioned in the very same verse as Tartak (2 King 17:31). Whoever Tartak and these other gods were, they were fallen gods, corrupt and wicked. And if that was the state of all these rebel angels, no wonder the Old Testament so frequently repeats, “Do not worship other gods” (2 Kings 17:37).

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month