What is Goshen in the Bible?

The short answer

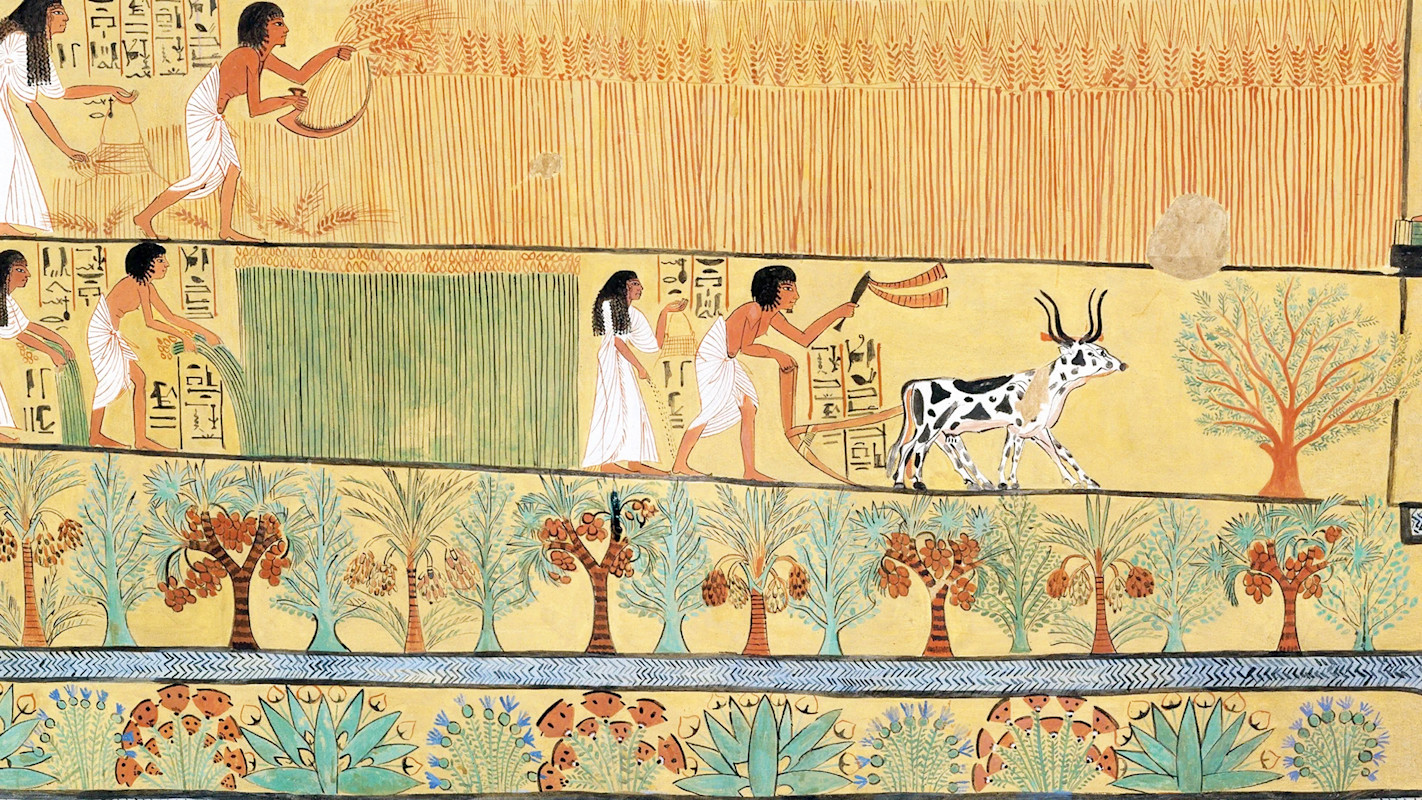

Goshen was a region in ancient Egypt, north of Nile in a delta, on the coast of the Mediterranean sea. It is the region that Pharaoh gifted to Joseph as the place where he could live with his people - the ancient Israelites. Eventually the Israelites were forced to leave Goshen and begin their famous wandering Exodus to Israel.

The “land of Goshen” is the name of the region that the pharaoh of Egypt gives to the Israelites when they settle in Egypt. This is the culmination of the story of Joseph, an Israelite sold into Egyptian slavery by his brothers. He later rises in the ranks of Egypt so high as to become second to Pharaoh himself. Eventually he reconnects with his brothers, forgives them for what they did, and has them return to their father and invite the entire family to come settle in Egypt:

“Hurry and go up to my father and say to him, ‘Thus says your son Joseph, God has made me lord of all Egypt; come down to me, do not delay. You shall settle in the land of Goshen, and you shall be near me, you and your children and your children’s children, as well as your flocks, your herds, and all that you have.” Genesis 45:9-10

Land of Goshen, Egypt

Jacob’s family – including his animals, servants, eleven other sons and their wives and children – all come to settle in the land of Goshen, where they prospered. Part of this was because Goshen itself was a good land. When suggesting that Jacob’s family relocated to Egypt, Pharaoh says, “The land of Egypt is before you; settle your father and your brothers in the best part of the land; let them live in the land of Goshen” (Gen 47:6). Goshen was a particularly good spot, as it was at the north of Nile in a delta, on the coast of the Mediterranean sea.

Another element in their success was that Pharaoh put them in charge of his animals. “If you know that there are capable men among them,” Pharaoh adds to Josheph, “put them in charge of my livestock” (Gen 47:6). The children of Israel were experienced herdsmen and were able to take up a role in Egypt as tending to the livestock, a job that resulted in considerable wealth. This is not very intuitive to modern people, but you have to understand that animals were (and still are) an important source of meat, nutrition, hides, and milk. Having control over many animals was identical with having great wealth. It’s no wonder that so many ancient texts like the Old Testament describe people’s wealth in terms of the number of animals they owned.

How long were the Israelites in Egypt?

The Israelites, as is well-known, did not remain in the land of Egypt. Jacob’s already large family (twelve sons and their wives and children) kept growing. It grew so much that in time it became its own distinct people group – the Israelites. They were called this because Jacob – the father of all the twelve sons – was named “Israel” by God (Gen 32:22-31). Eventually, as recounted in the book of Exodus, there was contention between the Israelites and the Egyptians, which ultimately resulted in the Exodus (the “way out”, in Greek). The book of Numbers, later in the Old Testament, states that the Israelites lived in Egypt for four-hundred and thirty years (Exodus 12:40-41).

That is the Biblical account, but what is the consensus of scholars? As you might imagine, scholars disagree about the exact historicity of the Biblical accounts for three reasons:

Some of the timelines in the Biblical accounts are obviously incomplete or out of order

Not everything claimed in the Bible can be independently verified by other historical sources

Many of the texts of the Bible were written long after the recorded events took place.

Does that mean that the Bible is “wrong” and can’t be trusted? That would be too hasty of a conclusion to come to.

There are two mistakes that people make about the Bible – even, or especially, certain kinds of scholars. The first is to view the Biblical narrative with extra suspicion on the basis that it makes “religious” claims. The assumption is that, because the Bible makes religious or supernatural claims that are “obviously” false, anything the Bible says about history must be treated as suspicious unless it can be proven by some other, non-Biblical source from the ancient world. While it’s a good scholarly practice to try to look for consensus among ancient texts (especially that lines up with archeology), many scholars raise the bar unfairly high for evidence from the Bible because they have a bias against Christianity, or Judaism, or both. Less severe, but more common, is the idea that many normal, well-meaning people have, which is that anything ”spiritual” or “supernatural” can’t be proven or verified, but must simply be a matter of pure “faith” or “belief”. Or they’ll assume that all ancient people were “superstitious” and ignorant, and that’s why they believed in the “obviously” fake things that they did.

I think that this is unfair to ancient people groups. Ancient peoples were often quite sophisticated in their thinking – in many ways, much more than modern people. Long before electricity was discovered they had developed quite sophisticated mathematics, capable of such feats as accurately calculating the diameter of the Earth. Ancient Egyptians especially were able to build structures like the pyramids that are incredibly impressive, even by today’s standards. There are many elements of their architectural achievements where we still don’t understand how they were able to build. Yet at the same time these were people who believed in gods and spirits. If we’re being honest, it’s quite difficult to dismiss the ancients as “superstitious” and “ignorant”. There are quite rational reasons to believe that they had a good sense of the world, and that should invite us to take their claims about the spiritual world a bit more seriously. The existence of actual spirits is at least as good a hypothesis as the belief that it was aliens who came down and taught the Egyptians how to use tools. Despite the fact that there is objectively less evidence for aliens than for spirits, modern people prefer an aliens theory because it sounds more “scientific” rather than “spiritual”. But that is part of our modern bias.

The second mistake people make when considering the Bible has to do with our modern bias towards things that sound “scientific”. When modern people think of writing down an account of something that happened, we tend to value accuracy rather than truth. We want to have a certain kind of “objective” recounting of names and dates, precise measurements, and so forth. Because journalism was so focused for so many decades on presenting “unbiased” narratives, the whole idea of the author adding his or her own personal interpretation of the events that were being reported has become very much frowned upon.

But ancient people did not think like this at all. For ancient people, truth was the most important thing – not facts. Facts are just the answer to the “what?” question. Truth is the answer to the question, “what does it mean?” If I asked you, “how was your day today?” you wouldn’t start telling me a minute-by-minute account of the facts of your day. You know that’s not what I’m asking. You would probably start by saying, “It was a good day” or “it was a bad day” and then you’d explain why. In other words, you’d start telling me a story, which is different from an account of the facts because a story has a specific meaning to it. Moving facts around in order to fit the meaning or deeper truth of a story was seen as a universal practice among ancient authors.

You see this most clearly when you compare the four different gospel accounts to one another. Many of the details of the different accounts don’t line up, and they even contradict each other at many points. The order that Jesus experiences his temptations in the wilderness are different depending on which gospel you read (compare Matt 4:1-11 with Luke 4:1-13). In Matthew and Mark’s accounts, both of the thieves who are crucified with Jesus mock him, whereas in Luke’s account, only one of the thieves mock him while the other repents and is told that he will be with Jesus “in paradise” (Luke 23:39-43). Does that mean the gospel is “unreliable” because it “contradicts” itself? Not at all. Again, it was a universally accepted practice among ancient writers to move the facts around to help support their point. Not because they didn’t care about the truth, but because they cared about truth more than mere facts.

This is something we always have to keep in mind about the Bible. To hunt around the Bible to see where facts are out of place, or over-emphasize the factual accuracy of this or that detail, is to be doing something totally different than the Biblical authors were trying to do.

When you take all of this together, you start to realize that you can’t just measure the Bible like you would a historical or journalistic account of a modern event. Biblical interpretation is quite a different matter, and the early Christians were very much aware of this. If you’re interested in learning more about how ancient Christians specifically thought about the world, including how they interpreted the Bible, I recommend Journey to Reality: Sacramental Life in a Secular Age.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month