Where is Amenadiel in the Bible?

The short answer

Amenadiel, the “older brother of Lucifer,” is not in the bible. He was created for a popular work of fiction in the 17th century, over a thousand years after Jesus lived. Amenadiel is more just a character of pop culture (and now, of television) than anything real or historical.

Amenadiel is a figure from the DC comic Lucifer – a Neil Gaiman comic subsequently released as a 6-season television series in 2016. Amenadiel is portrayed as the older brother of Lucifer and the eldest of the angelic siblings, and the presence of such a character has inspired a host of internet searches about who Amenadiel “really is” and whether there’s any substance to the depiction of these angelic characters. This happens every time a movie tries to dip into themes that are, in a sense, too big for it.

Religion and pop culture have always had a weird relationship. Dante’s Inferno is maybe the earliest example of an artistic portrayal that overshadowed the original source material that inspired it in the minds of the common man. The whole idea of hell as a place of specific tortures and punishments for people, or of having various levels, or the nearly comical image of devils in red tights poking sinners with pitchforks – none of this is in the Bible, and while there are more details about the afterlife in the writings of later church fathers, none of it comes close to these almost comically specific images that emerged in later pop culture. The 2016 show The Good Place, which depicts people’s good and bad deeds on Earth being measured with a literal point system, and then rewarded or punished, is just the most recent descendant of the imagery in Dante.

Virgil guides Dante through Hell (figures in upper left) in this 1850 painting by Bouguereau

But it’s not a simple matter of pop culture going too far. What’s interesting is that, however inaccurate the imagery or ideas may be, there’s a kind of aesthetic that has remained resonant with people that continues to be passed down through these pop cultural depictions. Even the most hardened person has a moral sense that justice exists and that if people really were held accountable for everything they did, well, it wouldn’t be pretty.

The reason for this resonance is – whatever the statistics say about modern people’s lack of traditional religious faith or poor church attendance – it’s a fact that all of the imagery and core ideas of the Western world were shaped by Christianity. Medieval and Renaissance painting, music, and literature were especially influential on modern art and, from there, on popular culture. Ideas about sacrificial love – that things need to get worse before they get better – or even the idea of a set of universal human rights – all of these ideas were first introduced into the West through Christianity. In a real sense, we in the West don’t know how to think about the world in any other way. Even the most “unbelieving” of us still resonate much more with the Christian ethics of universal human dignity than the truly heartless brutality of our distant pagan ancestors.

So when we ask a question like, “Who is Amenadiel?”, we’re really asking two questions. First, we are asking about what’s “official” or “canon” to the Bible and/or traditional Christianity. That’s what you might call the “factual” level. But at a different level, we’re asking about something more general: what truth is there in the idea of a spiritual world, of archangels and powers, in sin and salvation, and so on? What part of the “spirit” of a show can we believe in? When Tolkien was writing his mythology for The Lord of the Rings, for example, he was under no illusions about the fact that this was fiction. But in one of his letters, he wrote that he wanted to offer a look at a spiritual world that a Christian could “believe in," not in the sense of confusing it with the facts, but in the sense of its spirit world having a deeper truth about the world.

Who was the angel Amenadiel?

Archangel Gabriel close-up in The Annunciation by El Greco (circa 1570 AD)

That said, for most of Christian history, the church traditionally held that there existed other angelic beings and went so far as to name them. Its sources for these were varied, but were largely based on Jewish writings from the Second Temple period, like the Book of Enoch. Enoch is a curious book because it was not included in the canon of scripture but is cited as authoritative by both the writers of the New Testament and the early church fathers. The short version of the story is that there’s a sense in which the Book of Enoch really is authoritative in Christianity, but with a different kind of authority than the canon of scripture.

If you do a quick Google search, you’ll run into all kinds of articles that attempt to tell you that Amenadiel is mentioned in the Book of Enoch, which, if true, would give a certain level of legitimacy to the name. But you can’t trust everything you read on the internet! Amenadiel is not mentioned in the Book of Enoch.

Where does the name come from? It comes from a document called The Lesser Key of Solomon, a grimoire - that is, a spellbook – that includes many lists of demons and other malevolent spirits, their roles and ranks, as well as ways to seal, conjure, and summon these creatures. Amenadiel is listed as one of the “emperor” demons, which were divided into the four cardinal directions, with four “king” demons under the rule of each of the “emperor” demons. Amenadiel is listed as the “Emperor of the West”.

The Lesser Key of Solomon (this edition printed in 1916)

Well, if the Book of Enoch was in some sense authoritative even though it wasn’t part of the canon of scripture, what can we say about this Lesser Key of Solomon? In short, its authority is very vague. The Book of Enoch was compiled somewhere between 300 and 200 B.C. It was old enough to become influential on the New Testament authors. But the Lesser Key of Solomon is a seventeenth-century spellbook – a millennium and a half older than the Gospels. It would have been impossible for this book to be an influence on the Gospels, the early church, or the development of Christianity.

But why is it called the “Key of Solomon” if it’s so much older than him? The Lesser Key is what scholars call pseudepigraphica, which is a Greek word that just means “falsely written”. That means it wasn’t actually written by Solomon but was attributed to him in the name. This was a common practice in the ancient world: people would attribute works to older authors, not on the pretense that they were really authored by those people, but to identify the author’s work as being part of the same tradition (the Book of Enoch is the same way, as it obviously wasn’t written by Enoch, who lived before the time of the Flood of Noah).

So what tradition is the Lesser Key drawing on? The title is a reference to an older text, called the Testament of Solomon, which tells a kind of “extended” story about how Solomon was able to build the famous temple in ancient Israel. The story claims that he did this through the aid of a magical ring given to him by the archangel Michael, which he used to summon and command demons to be his slaves.

It’s very easy to dismiss both the Testament of Solomon and the Lesser Key on which it is based. Both are pseudepigraphical. The Lesser Key was written far too late to be remotely considered as authoritative for Christian tradition. It is much more obviously the product of the magic-crazed early modern period of witch hunts and spell books. Likewise, both the author(s) and date of the Testament of Solomon are extremely difficult to pinpoint. The text seems like a compilation of many sources. Unlike the Gospels, which are, by the standards of the ancient world, extremely easy to trace, it’s difficult to say that these later works have really anything “authoritative” to say about the Christian tradition or its theology. Almost certainly, the name “Amenadiel” was pulled by Neil Gaiman while he was leafing through the Lesser Key and looking for names that sounded cool. The character of Amenadiel in the series certainly bears no real resemblance to how the figure is described in the Key of Solomon.

The spirit of the truth

2013 cover of Book 1 of Lucifer comic book

If we take a big step back and squint our eyes, the main thing that’s true in this sense about shows and comics like Lucifer is the existence of many spiritual beings. While the Bible, again, doesn’t have this spiritual world as its main focus, there are hints all throughout the Old and New Testaments of a “divine council” of spiritual beings – with God at the head – that governs and interacts with the mortal realm. Granted, if you want to only look at the text of the Bible, there isn’t always a lot to go on, but if you look at the other historical writings – the Jewish literature from second-temple period and the writings of the early Christians – you’ll quickly realize that these ideas were widely accepted among the Jews of antiquity and the early Christian church. In fact, the reason that these ideas are only briefly touched on in the Bible was almost certainly because the authors assumed that their audiences were already familiar with them.

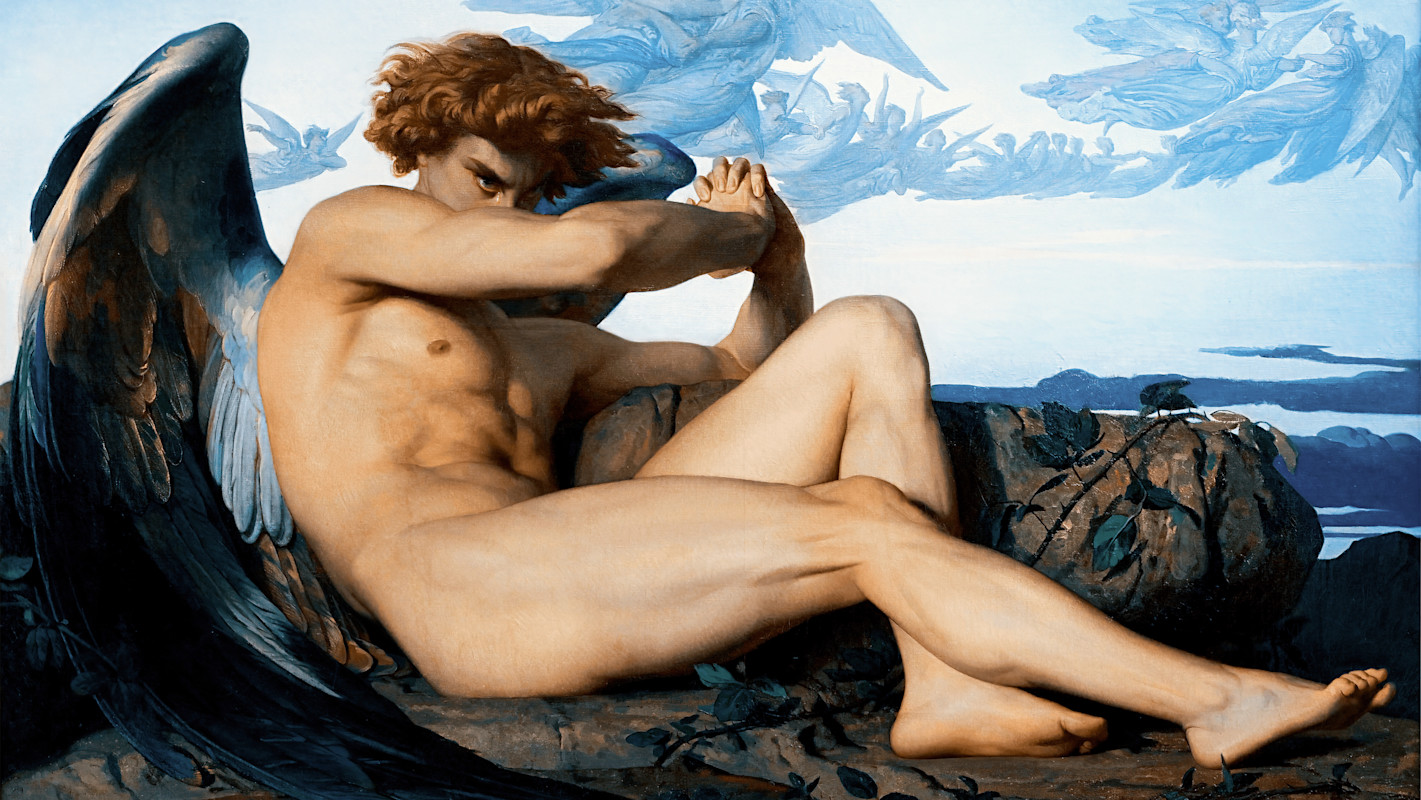

The second thing that’s a central part of the content of the Lucifer story that’s also true in “the real world” is the fact that angelic powers can succumb to temptation and “fall”. The Book of Enoch presents an account of how this happens – probably the most influential account ever written, and which was assumed by the New Testament authors and early Christians (again, you can read more in our Enoch article).

But the whole idea of fallen angels going on adventures to redeem themselves, or of coming to Earth and working normal jobs, is where pop culture goes too far. Something that none of these texts mention is the possibility for fallen angels to repent – either because they can’t, or because they don’t want to. In fact, the idea of fallen angels wanting or trying to repent is a story that’s not really present in ancient texts; it’s a fixation of modern writers.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month