The short answer

The Book of Enoch is not in the Bible, and should not be read as inspired scripture. But if you read it through the lens of the Biblical canon you may find all sorts of fascinating depth in both the Old and New Testaments that you may have never seen before.

If you’ve heard of the Book of Enoch, you probably know it’s very weird. It’s an ancient document that claims to be written by the great-grandfather of Noah, a mysterious man who is mentioned in the Bible as being “taken away” – presumably into heaven – by God. It lists the names of various angelic beings (called “the Watchers”); it describes half-human, half-demonic hybrids; it discusses various magical arts; and it features a variety of “angelic” knowledge about the divine nature of the cosmos.

What’s even weirder is that the Book of Enoch doesn’t deviate from the other major themes in the Bible. Enoch not only reinforces other Biblical themes but is itself referenced multiple times throughout the New Testament, especially in the Gospel of Matthew and many of the epistles. It’s almost like the authors of the New Testament regarded the writing (or at least the story of Enoch) as – in some way – authoritative.

It would be very easy to see the Book of Enoch as a compilation of “secret” lore, especially since it seems to have been so influential on the Biblical authors. But if you start talking about the names of the fallen angels, their domains of magic, and secret cosmic lore, you’re probably going to raise a lot of eyebrows. This is why some people are concerned that the Book of Enoch is – from a spiritual perspective – potentially dangerous, and that it’s something to stay away from. How true is that?

What is the Book of Enoch?

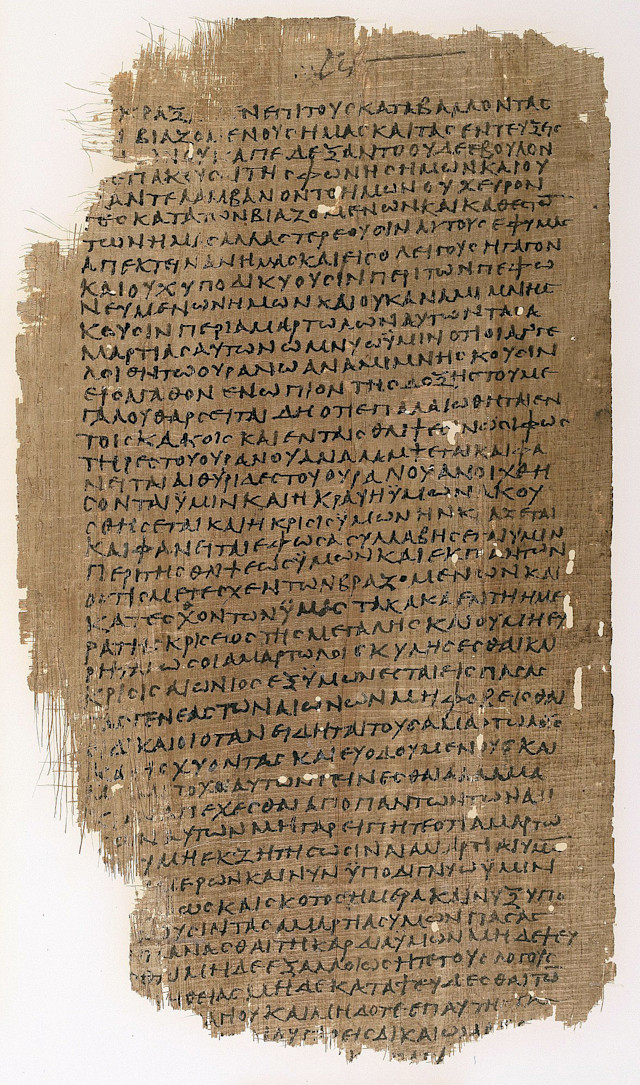

Ancient manuscript of the Book of Enoch in Greek. World History Encyclopedia

The Book of Enoch was the most prominent of these writings. Written in around 300 B.C., the book tells the story of Enoch and the vision he had of the heavens. Most famously, Enoch is an expansion upon the story in Genesis 6, in which the “sons of God” have sexual intercourse with human women and beget the “giants” (or “nephilim”) who terrorize the earth. The Book of Enoch goes into much more detail about this story, explaining who these spiritual creatures were, how and why they fell, and the kinds of things that they taught their wives and sons – such as how to smelt metal to make weapons, the use of magical spells, and the art of mixing potions. Because the world becomes corrupt and lawless as a result of these actions, God sends the archangels Michael and Raphael to round up the rebel angels and restore order to the world. Finally he sends the Great Flood to cleanse the land from its impurities, saving only Noah and his family in the process. Along the way, an angel takes Enoch into the heavens and shows him the inner workings of the cosmos.

Who are the Watchers in the Bible?

The angelic creatures who fall in the Book of Enoch are known as “the watchers”, and the event of their fall is usually known as “the fall of the watchers”. It is traditional to line up the Book of Enoch with the same story in Genesis, and the understanding is that these angelic beings were sent to watch over and steward the Earth – hence “watchers”. But because they fell they became the source of chaos and moral anarchy. The text of Enoch describes their intercourse with human women as “defilement” (Enoch 3:7), that their children become horrible giants who “consumed all the acquisitions of men” and “devoured mankind” (3:9) and that they “sin against birds, beast, and reptiles, and fish, and to devour one another’s flesh, and drink the blood” (3:10). The watchers also teach hidden lore to human beings, lore that is at best a little problematic, including “charms and enchantments” (3:8) as well as metalworking for the purpose of weapons of war. Because of all this, the Book of Enoch says that “there arose much godlessness, and they committed fornication, and they were led astray, and became corrupt in all their ways” (3:12), and that “as the men perished, they cried, and their cry went up to heaven” (3:14). This is what happens when those who were meant to watch over the Earth instead become corrupted: the world begins to fall apart.

Who wrote the Book of Enoch?

The simple answer is that we don’t know. The Book of Enoch presents itself as being written by Enoch himself, the grandfather of Noah. The opening words are, “The words of the blessing of Enoch” (1:1). Yet the oldest manuscript evidence we have for the book is from 300 B.C. – a very, very long time after the Great Flood of Noah’s time, by thousands of years at least. It’s hard to image that Enoch himself was around for that long afterward, especially since the Bible depicts him as being “taken away” by God and not dying (Gen 5:24 and Heb 11:5).

Those who wrote the Book of Enoch probably weren’t trying to deceive readers into thinking that it was written by Enoch.

This gets us to an important point. The Book of Enoch probably wasn’t entirely authored by one single person. The account in the story and the ideas about cosmology, the fallen angels, etc., seem to be ideas that had been accepted among Jewish thinkers for quite a while – and continued to be influential into the era of the New Testament and beyond. The Book of Enoch, therefore, is more of a compilation of a longer tradition of Jewish thought, and is authoritative in the sense that it’s an accurate preservation of these ideas. But we have no evidence that it was actually written by Enoch.

How was the Book of Enoch used in the Bible and early church?

There are many references to Enoch in the Biblical writings. One obvious place is when Hebrews references Enoch being taken up into heavens by God (Hebrews 11:5). But the biggest might be where the Book of Jude references Enoch as a prophet:

Now Enoch, the seventh from Adam, prophesied about these men also, saying "Behold, the Lord comes with ten thousands of His saints to execute judgment on all, to convict all who are ungodly among them of all their ungodly deeds which they have committed in an ungodly way, and of all the harsh things which ungodly sinners have spoken against Him.”

Jude 1:14-15 (NKJV)

Compare this to the Book of Enoch itself:

And behold! He comes with ten thousands of His holy ones to execute judgement upon all, and to destroy all the ungodly, and to convict all flesh of all the works of their ungodliness which they have ungodly committed, and of all the hard things which ungodly sinners have spoken against Him.

Enoch 1:9 (source)

There are an incredible number of these references and parallels to the Book of Enoch throughout the Bible. Further, some scholars have given very compelling arguments that the New Testament authors were heavily influenced by Enochian themes and imagery. In her book on the subject, Amy Richter has argued that a major theme in Matthew’s gospel account was to bring closure to the story that began with the fall of the watchers in Enoch. The implication is that the “wise men” – the magi – were Persian magic-users who still practiced certain magical arts learned from the fallen angels, but whose art nevertheless brought them to the correct understanding of Jesus’ coming into the world.

The Magi - Henry Siddons Mowbray - 1915. Richter sees the magi of the Book of Matthew as Persian magic-users who had magical arts learned from the fallen angels.

What’s more, major figures among the early church fathers reference Enoch as though its narrative was authoritative. These figures include such prominent Christians as Origen, Tertullian, and Sts. Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Clement. The Book of Enoch is perhaps the most important source for these early Christian fathers in their explanation of demonology, for they did not view the gods of the pagan nations as unreal. On the contrary, they believed that they were in fact real spiritual beings who had fallen from heaven because of their corrupt desires – and they cited the Book of Enoch to validate their beliefs.

Why isn’t the Book of Enoch in the Bible?

Given how influential the Book of Enoch was on the early church, it seems like Enoch should be a part of the Bible – yet it isn’t. Because of this, many people think there must be something wrong with the Book of Enoch. After all, if it’s so important and influential, why isn’t it a part of scripture?

In order to understand this problem, we need to first take a step back and ask the broader question, “what do we mean by scripture?” The word itself, in a vacuum, is ambiguous. It’s a Latin word that literally means “writing”, and the Greek equivalent (graphe) is used in a variety of different ways in the New Testament, sometimes referring to the gospels or epistles, sometimes to the Old Testament, and sometimes to things that are neither.

Modern-day Christians, however, use the word “scripture” with a very specific set of ideas in mind – almost like it’s a technical term. For many people, the idea of “scripture” is identical with “the Bible”, and their idea of the Bible is that it’s a single document of ultimate authority that is completely self-contained, exhaustive, and self-interpreting. Many people add that because the Bible is “the word” of God, it is somehow unable to be incorrect in any way, or that it’s the ultimate standard for the religion of Christianity, or that Christianity as a religion started from or emerged from the reading of the Bible. When you think about the Bible in this highly technical or legalistic way, the question becomes very simple: either something is in the Bible or it isn’t; and if it isn’t, then it’s potentially untrue, misleading, or even unsafe to read.

The major problem with this way of thinking about the Bible is that it wasn’t how ancient Christians thought about the various texts of scripture at all. Christianity did not start with a book, but with a man – Jesus – a man who didn’t write anything down. Christ came first and the written texts came second. This personal encounter between God and human beings has always been the primary way God interacted with people throughout the Christian story: from God’s covenant with Abraham to God’s calling of Moses in the burning bush to God’s choosing of Mary to be the God-bearer of Christ, Christianity has always been based first on personal encounters and only secondarily preserved through texts. The idea that the text of scripture is the source of Christianity, or that it’s the primary way of adhering to Christianity is much more of a Muslim or Rabbinic Jewish way of thinking about religion.

Early Christians believed that all truth was God’s truth.

Defining the canon of scripture

The phrase we should define here is “canon of scripture”. The word “canon” is an old Greek word that means “rule” in the sense of something that measures, e.g., a “ruler”. The point of a ruler or tape measure is to be able to measure other things by it. So having a “canon of scripture” means that you have a set of writings by which you measure other writings or ideas. It’s not that these writings are the only things that are true, it’s that they’re a kind of baseline or foundation for specific truths – in the same way that a ruler is a baseline for certain measurements. In this case, the canon of scripture in Christianity is an authoritative baseline for measuring other truths against. This is why Christians have historically rejected later gospels like the Gospel of Peter or Mary Magdalene, because when you compare them to the canonical gospels, they don’t line up with the same theological content or themes the way that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John line up with one another. They don’t, in other words, “measure up” to the standard.

How did the early church choose which writings were canonical?

You can see now how a “canon of scripture” is more complex than simply choosing which books are “right” and which are “wrong”. That’s how we think about modern media in which some movies or books belong to an author’s imagined world and others don’t. Christians have historically read and used all sorts of writings as edifying, valuable, and authoritative in different ways (especially the writings of the saints), but the church wanted to preserve a certain set of texts from the first generation of people who interacted with Jesus as a kind of standard or rule by which to measure other texts. Just because a text wasn’t included in this standard doesn’t mean it is automatically false or wrong. It just doesn’t fit the criteria for being a canon or ”ruler”.

Putting all this together, you can see now why a text like the Book of Enoch wouldn’t be included in the canon of scripture. The fact that Enoch is a pseudepigrapha, that it’s more of a compilation of a tradition rather than the source of one, and that it had a variety of anonymous authors, are all reasons why – though valuable – it is not a good candidate for being canon. Enoch needs more interpreting and sorting out because all of these factors make it somewhat less reliable and clear than the canonical texts whose origins and textual history we understand much better. Enoch remains, in a real sense, authoritative, but it has a kind of secondary authority, one that needs to be filtered through the lens of the primary authority – the canonical scriptures. In places where Enoch and the canon line up, we can benefit from Enoch providing additional depth or detail; but where Enoch contradicts the canon, we fall back on the canon as the primary authority.

What’s wrong with the Book of Enoch?

Intrinsically, there’s nothing “wrong” with the Book of Enoch. It is an important ancient document that adds to our knowledge about the period and expands upon certain ideas in the Bible. Indeed, if it was authoritative for the New Testament authors and the early church fathers, then it should be something we take seriously as well. But as Christians we must read it in the right way.

There are two major mistakes that you could make about the Book of Enoch: reject it entirely or accept it entirely. Many reject it entirely on the basis that, since it is not in the canon of the Bible, it is therefore false or misleading. To take this attitude would be to go against the New Testament authors and the early church. But you could also make the opposite mistake. You could think that, since the Book of Enoch is in some sense authoritative, it is therefore just as authoritative as rest of the canonical scriptures – or perhaps even more so because it helps to clarify some of the more vague parts of certain Old Testament passages. But if you did this, you’d also be setting yourself against the early church, because they did not include Enoch in the canon of scripture.

To read the Book of Enoch correctly, therefore, you should take it seriously but read it through the lens of the Biblical canon. And if you do that, you’ll find all sorts of fascinating depth in both the Old and New Testament that you may have never seen before. Just don’t get too carried away.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month