The short answer

Christ's flipping of tables in the Temple happened because the Jews had turned the Temple away from its original purpose. In this way, flipping the tables was a prophetic act predicting the Jewish Temple's destruction, with Christ's own body taking its place. Christ's body was also destroyed, but rose from dead three days later as the new "temple", the new way for us to have connection to God.

Whether you’re a Christian or not, it’s an indisputable fact that Jesus is the number one most influential person to ever live. One easy way to measure this is to measure the number of books that have been written that are based on a particular figure. When you measure it that way, Jesus ranks very comfortably in the number-one spot (number two is, apparently, Abraham Lincoln).

When you’re that popular, it’s easy for stereotypes to arise, and probably the most common one about Jesus is that he was an advocate for radical peace, tolerance, compassion, and so on (or even just as a “nice guy”). This is maybe why people are so fond of bringing up the story in the Gospels (three of them, at any rate) which describe Jesus going into the temple and flipping tables. It doesn’t fit into the stereotype of the peace-loving Jesus, and people capitalize on this supposed incongruence in all sorts of ways. Without getting too much into all the different possible interpretations, what can we say for certain as a baseline?

Jesus and the money changers

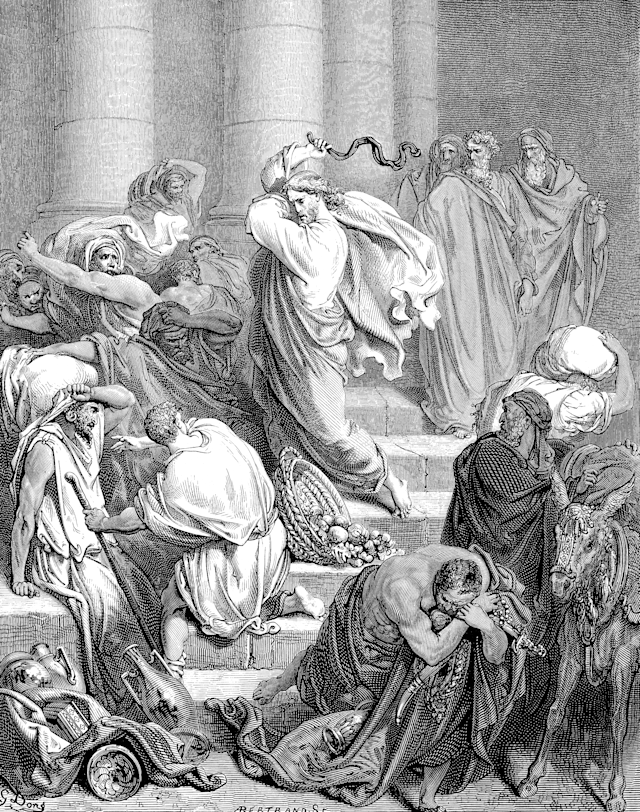

Money changers driven out of the Temple - 19th century engraving by Gustave Dore

Mark’s account adds that Jesus “and would not allow anyone to carry merchandise through the temple courts” (Mark 11:15-18). In John’s version, Jesus actually makes a whip first and then (presumably) uses it to drive out the animals (John 2:15). In both Mark and John, there’s specific mention of “those who sell doves”, where Jesus turns over their benches in Mark’s account and specifically tells them in John, “Get these out of here. Stop turning my Father’s house into a market.”(John 2:16).

What is going on here, practically speaking? In the second temple period of ancient Israel, worship was conducted through the sacrifice of animals. Those who were traveling to Jerusalem to worship in the temple needed animals to sacrifice, and that’s why there were animals available to purchase. The doves in particular were the “cheap” animals, and were available for those who couldn’t afford a sheep or an ox.

So if animal worship was necessary for temple worship, what was the issue with people selling animals? The most basic, obvious issue has to do with the money-changers. The people attending the temple were traveling from distant lands and had different types of money, which had to be exchanged in order to make purchases. The way you can take advantage of people as a money-changer is by charging a large fee for the exchanging of the money, effectively “ripping off” the people who came to the temple to worship. We can intuit that this was what was going on by Jesus’ own accusation, as he calls it a “den of robbers”. These fees would be especially felt by those worshippers who were too poor to afford anything other than the doves, which is potentially why Jesus specifically addresses the dove-sellers in his accusations. To put it in the language of our times, something that was supposed to be a house of worship had instead become a place for exploitive business practices.

Jesus flips tables. Should you?

It’s easy to read this scene as an example of Jesus getting angry and think that this sets an example for us to do the same when the right conditions are met. People use the phrase “righteous anger” for the times when you’re angry about something, but because you’re angry on behalf of something that’s good and true, you are allowed to get angry, even to act out. The fact that you’re angry over a just cause, in other words, gives you permission to act out in this way.

This way of thinking is problematic, and many people recognize it as such. The main reason is because it seems selfless but is actually the opposite. You think you’re acting out of duty or passion for goodness and justice, and therefore you aren’t selfishly indulging your own anger, but how do you know that? If you are the one who decides whether something is just or not, then there’s a danger of becoming a hypocrite without realizing it.

There are certain natural temptations that arise when you put yourself in the position of the judge over what’s right and wrong. It’s easy to build criteria in your mind where the things other people do are unjust and wrong, whereas the things that you do are just and right.

This is especially a temptation when you have a strong sense of your own identity as someone who cares about justice and rightness. The more you think of yourself as that kind of person, the easier it is to automatically assume that your own actions are just and right. So if you get angry about something, your anger is probably justified because it’s righteous anger!

In the end, you make yourself into the ultimate arbiter of justice and truth, which gives you a perpetual license to get angry and act out in all kinds of situations. “Of course I’m angry at this injustice!” you might say. But of course, this is a dangerous way to act, and can lead to the hypocrisy of justifying your own angry behavior but condemning that of others. Hypocrisy aside, at a more basic level it just gives you free license to indulge a vice.

But what about Jesus? You might say that because he’s God and therefore has perfect knowledge of all things, Jesus is able to perfectly judge what’s justice or unjust. Unlike you or me, he knows what’s just and righteous, and isn’t prone to (or even capable of) self-delusion. Therefore (you might argue) Jesus is really the only one who’s able to have righteous anger in this way. So maybe this passage is really about showing us that Jesus alone has the license to be angry because only he can do it perfectly.

But is it really right to say that Jesus was acting in righteous anger in the first place? It’s not like anger is necessarily a good thing – “wrath” is, after all, one of the seven classical sins. How do we understand Jesus’ anger?

The thing is, these Gospel passages don’t really say anything about Jesus’ emotional state. When you look at the accounts in these gospels, they don’t portray Jesus as having “a fit”. He doesn’t see something that so enrages him that he goes out of control and does a bunch of violence. In John’s account, he first makes a whip out of cords – in other words, he sits down to do something fairly deliberative, rather than acting out of uncontrolled passion. And the text never says that he whipped the people; presumably the whip was simply for driving out the animals. None of the accounts portray him as angry, out of control, or even impatient.

It’s true that he takes some pretty intense actions: overturning tables, driving out the animals, and making some pretty severe pronouncements about the bad practices that he saw. But the authors of the gospel passages don’t give any indication of what his emotional state was.

The reality is that sometimes you have to be severe in life, sometimes even to the point of putting on a show of anger, but the ancient Christian understanding of righteous anger was not “justified anger” but “dispassionate anger”. The idea is that, even if you have to put on a show of anger in order to get something done, the traditional teaching of Christianity is that you have to do this in a way that is dispassionate: in other words, self-controlled rather than out-of-control, self-less rather than self-indulgent. People indulge anger all the time because it often feels good to be angry, especially if you decide you are justified in it. It feels good to be mad at someone or something, because it makes you the “good guy”. Your anger becomes a kind of reveling in how you’re in the right and how everyone else is wrong.

But that’s not the portrayal of Christ that we see in these gospel accounts. What we see is Christ taking action – albeit, action of a somewhat severe variety – but deliberative, self-controlled, and clear. He speaks the truth, but not for his own satisfaction. He makes a show of anger, but remains in control. He condemns, but he isn’t cruel.

It’s true that Christ is God and has the authority or the “right” to do these things. It’s true that he’s the perfect judge of what is right and wrong. But when you start asking the question of how to imitate Jesus, what stands out about these passages is that the way he conducted himself inspired people towards the good, not – as it might seem at first glance – that he was condemning and tearing people down.

Notice that in Mark’s account, the text says, “And as he taught them, he said, ‘is it not written: “my house will be called a house of prayer for all nations”?’”(Mark 11:17, emphasis mine). And how do the people respond? “The whole crowd was amazed at his teaching” (Mark 11:18). So even in the midst of what appears to be a scene where Jesus is almost literally tearing something down, the deeper reality is that he is doing it with an aim towards raising the people up towards a higher good.

What did it mean? The fig tree is the Temple

One way to read Jesus’ act of flipping the tables is alongside the earlier passage in Mark’s account (Mark 11:12-14) where Jesus curses a fig tree and it withers. Right before the passage about the money-changers, Jesus encounters a fig tree that has not born any fruit, and he curses it, saying, “may no one ever eat fruit from you again” (Mark 11:14). Then he goes into the temple and turns over the tables. Later that day, when they left the city, Jesus’ disciples see the fig tree that he cursed. What had happened in the meantime? It had withered up in response to Jesus’ curse!

Because this passage is part of the same narrative as the money-changer episode, commentators tend to interpret the two together. The fig tree is a common metaphor for the people of Israel throughout the Bible (Hosea 9:10, Jeremiah 24, Jeremiah 8:13, Micah 4:4), and the fact that the tree bore no fruit is a symbolic representation that the Jews had not born spiritual fruit. Hence why the temple – the most holy place in ancient Israelite religion – had been turned into a place of worldly concerns (money) and even theft. And later, the religious authorities would arrest Jesus and put him to death – rejecting their messiah.

But there is a connection between the temple and the Jesus. Jesus refers to the temple as his own body. He says, “destroy this temple, and I will raise it again in three days” (John 2:19; see also Matt 26:61, Mark 14:58). Saint John, in his account, explains, “But the temple he had spoken of was his body. After he was raised from the dead, his disciples recalled what he had said” (John 2:22). When the Jews later destroyed the temple that was Christ’s body, he came back from the dead and overcame death itself.

A further meaning has to do with the literal destruction of the Jewish temple. Just a few decades after Christ’s death and resurrection, the Jews launched a revolt against the Roman rulers which began a series of wars. It culminated with the Roman emperor Titus laying siege to Jerusalem and destroying it, including the temple itself, in A.D. 70. The Jewish temple has not been rebuilt to this day, 2000 years later, invalidating the worship and religious practices of ancient Israel.

But the early Christians – the first of whom were themselves Israelites – had taken the core elements of Jewish temple worship and expanded it into a form that came to be called the Divine Liturgy. This was essentially the old worship practiced in the Jewish temple but transfigured and expanded into a full worship of God based on the revelation of Jesus and the teachings of his Apostles. And the Church is famously understood by Christians to be the body of Christ, not just metaphorically but literally through the practice of Communion (called the Eucharist).

Conclusion

So how do we understand all of this? Jesus cursing the fig tree and the historical realities surrounding the destruction of the Temple adds another dimension to what’s going on with Jesus overturning the tables in the temple. The withering of the fig tree for bearing no fruit has the same message as Christ flipping over the tables in the temple: the Jews had turned the Temple away from its original purpose, and so it was soon destroyed by the Romans for bearing no fruit. But in the same way that the Jews destroyed the temple that was Jesus’ body and he rose from the dead to even greater glory, the greater glory of the Christian Church was raised from the ashes of the destruction of the Jewish temple through the continuation of its worship in the Divine Liturgy.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month