The short story

Jesus went to Hell (see the scripture in Acts 2). He went there because he had a real body that experienced a real death. When Jesus went to Hell, he conquered it. Instead of being stuck there, Christ overcame Hell and set its captives free.

Because telling someone to “go to Hell” is an insult, the idea that Jesus went to Hell is probably a bit unnerving to many people. Yet the idea that Jesus descended into Hell when he died is, in fact, all over the writings of scripture, is assumed by the early church fathers, and was even stamped into the language of the Nicene Creed – the first universal declaration of what you had to believe to be a Christian. But how does this make sense if Hell is “the bad place” where you go to be punished? To understand this, you have to understand how ancient people thought about these things.

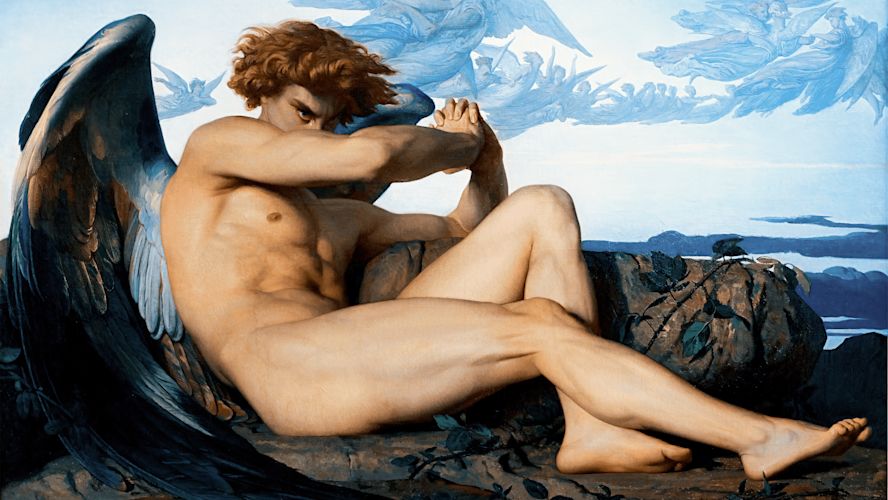

People tortured in the popular and false version of "Hell". 12th century manuscript.

The thing about this very specific picture of Hell is that it is not found in the Christian scriptures, nor is it really in the church fathers, nor is it how ancient people understood the afterlife. A better way to understand the ancient view of Hell is to use a different word: Hades.

Did Jesus descend into Hell or into Hades?

Hades is a Greek word used both for the realm of the dead and for the lord of the dead. You might see it referenced in the Bible as “the grave” or “the pit” (“sheol” in Hebrew). The idea is that this was the place where people went when they died. For the ancients, because everyone died, everyone went to the same place - namely, somewhere under the earth (seen in actually burying them in soil). Every ancient culture had this understanding that there was a place called Hades (Duat in Egyptian, Orcus in Latin, etc.) where all the dead went. And while there might be different places in the land of the dead that were better or worse depending on what sort of life you lived, everyone still more or less went to the same place – because everyone died.

It is in the context of this near-universal understanding among ancient people that we have to understand the references to Jesus’ descent. Jesus didn’t go to “Hell” exactly (again, hell is a modern word with lots of pop-culture connotations). Rather, how the early Christians understood this is that Christ went to the realm of the dead. He went to Hades.

What scripture says that Jesus went to Hell?

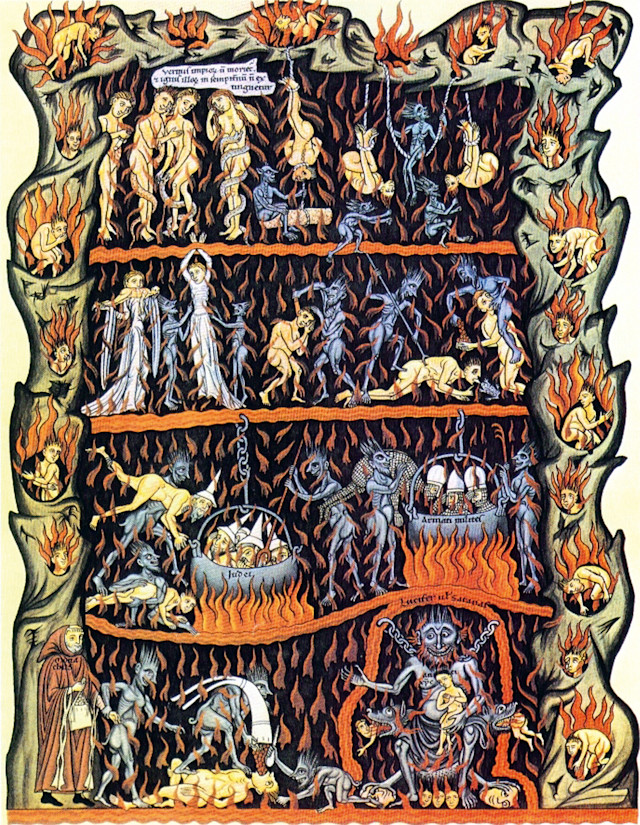

1425 AD manuscript: Joseph cast into the pit, Jesus placed into the tomb, Jonah swallowed by a fish (source)

But there’s more to it than that. The early Christians all had a very explicit understanding that, in descending into the realm of the dead, Jesus didn’t merely stop by for a visit. Christ invaded it and conquered it. This is because they understood the realm of the dead as a realm that was ruled over by the Devil.

If you go back to the account in Genesis of the Fall, you’ll notice an important detail. When the serpent induces Adam and Eve to sin, the serpent is the first one to be punished, and with a very specific punishment: God says, “You will crawl on your belly and you will eat dust all the days of your life” (Gen 3:14). Now, ancient people were aware that serpents did not literally eat dust. Genesis isn’t a folk account of “how the serpent lost its legs”, or something like that. There is spiritual meaning in this passage. “Dust” is the same word in Hebrew as “Adam”, and the two are frequently associated. Genesis describes the creation of man as, “Then the Lord God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being” (Gen 2:7).

The serpent (the Devil) will become the lord of death, “eating” all humans, for all humans will die.

Where did Jesus go when he died?

Jesus went to Hades when he died. What did he do there? He conquered Hades along with its ruler – the Devil. Many modern kinds of Christianity put the emphasis of Jesus’ saving act on his death on the cross, but the early Christians and the New Testament authors instead emphasised that it was Christ’s conquering of Hades that saved the race of mankind, because we had been enslaved to the devil. By going to the Devil’s kingdom and overthrowing it, Christ freed the captives who were in bondage there. St. Paul explains this in Hebrews where he says, “that through death He might destroy him who had the power of death, that is, the Devil, and release those who through fear of death were all their lifetime subject to bondage” (Heb 2:14-15). The Devil had the power over death, and the main effect of Christ’s descent was to release those who were under his power.

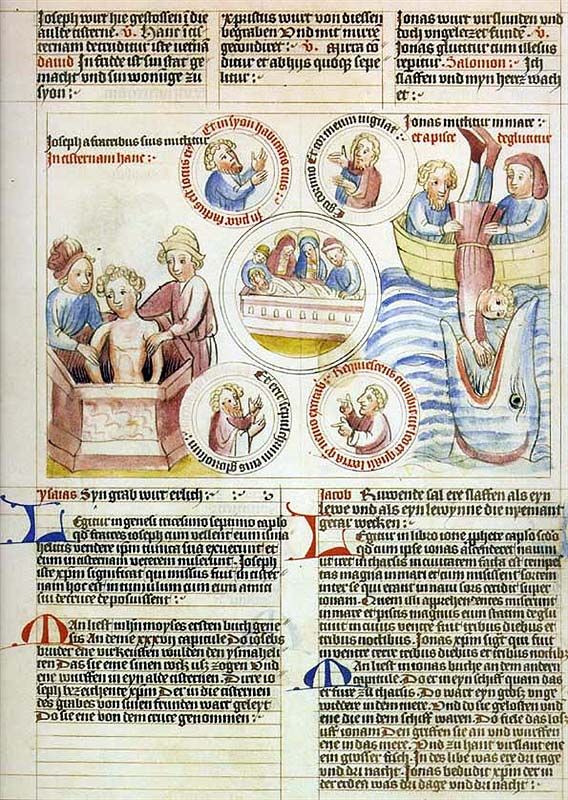

Christ setting free the captives of death, 15th century painting

St. John relays this in his Apocalypse. Christ declares, "I am He who lives, and was dead, and behold, I am alive forevermore. Amen. And I have the keys of Hades and of Death” (1:18). It was a common practice in the ancient world for conquerors to take as spoils of their conquest things that were important in the place they conquered, such as the keys to the city. In this case, Christ conquered death and now holds its keys; he dethroned the old lord who used to rule there, and now he is the one who rules over it. St. Paul talks about this in his letter to the Colossians. He writes of Christ, "Having disarmed principalities and powers, He made a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them in it” (Col 2:15).

This imagery is perhaps most potent in the Psalms. Psalm 24 describes Christ’s dialogue with the gatekeepers of Hades:

"Lift up your heads, O you gates!

And be lifted up, you everlasting doors!

And the King of glory shall come in.

Who is this King of glory?

The Lord strong and mighty,

The Lord mighty in battle.

Lift up your heads, O you gates!

Lift up, you everlasting doors!

And the King of glory shall come in.

Who is this King of glory?

The Lord of hosts,

He is the King of glory."- Psalm 24:7-10 (LXX 23:7-10)

The church doors are opened and all the faithful stream into the church yelling, “Christ is risen!”

That the church doors symbolize the gates of Hades is an additional bit of imagery: it is only by passing through the gates of death that we enter into the kingdom of God (represented by the church) and are able to take communion. All of us have to pass through death in order to receive life.

So yes, Christ goes to Hades – but as a conqueror, not as one conquered. And he is leading us to share in his glorious conquering of death and the devil. If you’ve ever wondered why the gospel is called “the good news”, now you have some idea as to why.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month