The short answer

The Bible doesn’t say anything about computer programs, especially not the ones we are designing now in the 21st century (obviously) but the biblical authors’ warnings about the pagan practice of creating gods and the bans on divination should make us cautious about this new technology.

What is “artificial intelligence”?

It’s important to understand that when engineers and programers talk about artificial intelligence, they aren’t actually talking about something that functions like the human brain at all. What we call “artificial intelligence” is not really a thinking mechanism, but something more like very complicated guessing. The better name for programs like ChatGPT is “large language model” (or ”LLM” for short). The essence of an LLM is that it takes a question you ask it and then tries to predict what combination of words and characters is the “right” response. It doesn’t do this on the basis that it’s actually able to understand language—not the way that humans understand language. What it does is it learns to recognize patterns across millions and millions of associations between words and combinations of words and then predicts which combination of words is the best response to the combination of words that you sent it. If you interact with such programs enough, it quickly becomes evident that the program isn’t actually thinking or communicating with you, it just keeps guessing at responses until it gets the one that satisfies you. This is why its responses can be outright wrong or even nonsensical, because—contrary to what you might have heard—it isn’t actually thinking.

ChatGPT, currently the most popular LLM (large-language model)

Fortune-teller reading the palm of a woman, 1936

This is more or less how a Large Language Model works. It takes a huge dataset of information and creates a model for how all of that data is related. Then it uses that model to make predictions about how words and phrases are related. Rather than call this an “artificial” intelligence, you might instead call it a kind of “simulated” intelligence: it isn’t really a mind or an intellect, it just simulates or creates the illusion of one.

While predicting what you want to hear is a little bit like fortune-telling, when you start ”asking” such a machine questions about the weather, the stock market, or world events, then you very much are engaging in a kind of divination. By creating LLMs, we’ve effectively built the most powerful divination method in human history; and though we might think we’re superior to our ancestors because we have machines while they were reading tea leaves or doing astrology, in reality, we’re all trying to do the same thing: predict the future so we can control it.

Divination and magic in the Bible

While simulated intelligence programs like these, for obvious reasons, are not mentioned in the Bible, divination very much is. The laws of the Old Testament forbid the ancient Israelites to use divination, along with the practice of magic and the construction of idols. It isn’t—as some people believe—that the ancient Israelites and Christians disbelieved in the reality of magic, demons, or the pagan gods. They absolutely believed in those things, but they were concerned about the danger and wickedness associated with them. What danger and wickedness? It has to do with the source of magic and the nature of these spiritual beings.

As I covered in my articles on the book of Enoch and the pagan God Tartak, the ancient Israelites and early Christians believed in the existence of the pagan deities. Their conception of the universe was that the highest God — the Lord of Hosts, the God of Gods, the God of Heaven — created all the lesser gods — the heavenly hosts, the “sons of God”, etc. These beings helped God oversee and manage the world, met regularly in assembly to discuss the affairs of the cosmos (see Job chapter 1), and even watched over specific nations. After the fall of the Tower of Babel, the Old Testament records that God divided the nations “according to the number of the sons of God” (Deut 32:8), which was traditionally understood to be a reference to the angelic beings that came to be called the “gods of the nations”. The issue is that, as recorded in the Book of Enoch, these creatures had their own “fall”: they became corrupt and enslaved to their appetites, and created the various religions of the pagan world as a means to obtain worship and sacrifices for themselves.

The medium Erik Jan Hanussen (middle) at a séance in 1928.

Divination and magical practices were, in large part, about interacting with these creatures and trying to obtain knowledge from them. Magical healings, wise advice, and especially predicting the future were all sought after when interacting with these imposter deities. But of course, if these creatures were in fact fallen angels, rebel gods, and usurpers of the highest God, then interacting with them is at — minimum — going to be dangerous. Such fallen creatures have no real interest in being honest, nor do they necessarily care about your wellbeing; they want what they want and so whatever they tell you might be misleading or intentionally dishonest. When you consider the number of absolutely brutal pagan gods who demanded things like human sacrifice and who frequently took out their anger on their worshippers, you can see why the Old Testament law of Moses would forbid any kind of interaction with them.

Algorithms are designed to tell you what you want to hear.

One of the big differences between this new kind of mechanical divination and the divination of our ancestors is the question of truth. Divination methods like reading palms, tea leaves, cloud patterns, or the motion of the planets all have something in common: they’re all about the natural world. Because ancient people believed in an enchanted world—the idea that all physical things had spiritual content—they believed that nature itself contained real spiritual truth that you could learn if you knew how to read it properly. To do divination well was about humbling yourself before nature and, in some sense, being a student of nature. In other words, the idea was that truth exists outside of you — it’s out there, in nature, and it’s something you can gain access to if you know how. You might think that these methods don’t work — that there’s no real truth in tea leaves, cloud formations, or the motions of planets. But it’s important to understand why people might think so: namely, ancient people fundamentally believed in truth that was bigger than them and could be known by them.

But with a modern intelligence simulators, the question of truth becomes very muddled. Remember that such a program works by guessing at the right response. It’s not really focused on the truth of the things it’s saying because it doesn’t actually have a way to verify the truth of anything — how could it? All it can do is guess based on pattern-recognition about what words and ideas are related to each other.

This means an LLM actually has a strong bias. First is the obvious bias that comes from the people who programmed it. But the second is the way it gets positive feedback for answers that the user likes and negative feedback for answers that the user doesn’t like. This is a very different criteria than whether something is true or not.

Truth, in other words, has been substituted for our desires.

Again, this is not as good as it sounds. In order to raise ourselves up higher than our merely biological urges, we have to do all sorts of things like delay gratification, make sacrifices, abstain from pleasure, and think long-term. The state of having all your impulses constantly and instantly gratified is a kind of hell: it reduces the human being to a mere animal and enslaves you in the dungeon of your urges.

The science of idol-making

The concerns we’ve discussed so far are assuming a more benign vision of this new technology. In fact, the above scenario is really just the minimum of what this sort of technology is capable of doing to us, especially when you combine it with virtual reality and the ability to generate any combination of images, sounds, and sensations. But there could be a much darker side to it. I want to end with a final concern, something that comes straight out of the Bible and the experience of the early Church. You might find it a little weird, but I think it’s something worth thinking about.

There are many places where the Biblical authors condemn interaction with what they call “idols”. In many modern Christian circles, this language has been used to mean things that you “worship” instead of worshiping God. If you get obsessed with a franchise, a hobby, or whatnot, someone might say that this has become your “idol” and you need to make sure you’re not giving it so much “worship” that it’s displacing God in your life. While it’s important to moderate your behavior and be self-aware of when things are disrupting your spiritual life, this was not what the Biblical authors were talking about when they talked about idols. In the ancient world, making and worshiping idols was a near-universal pagan practice that was understood in a very specific, very literal way.

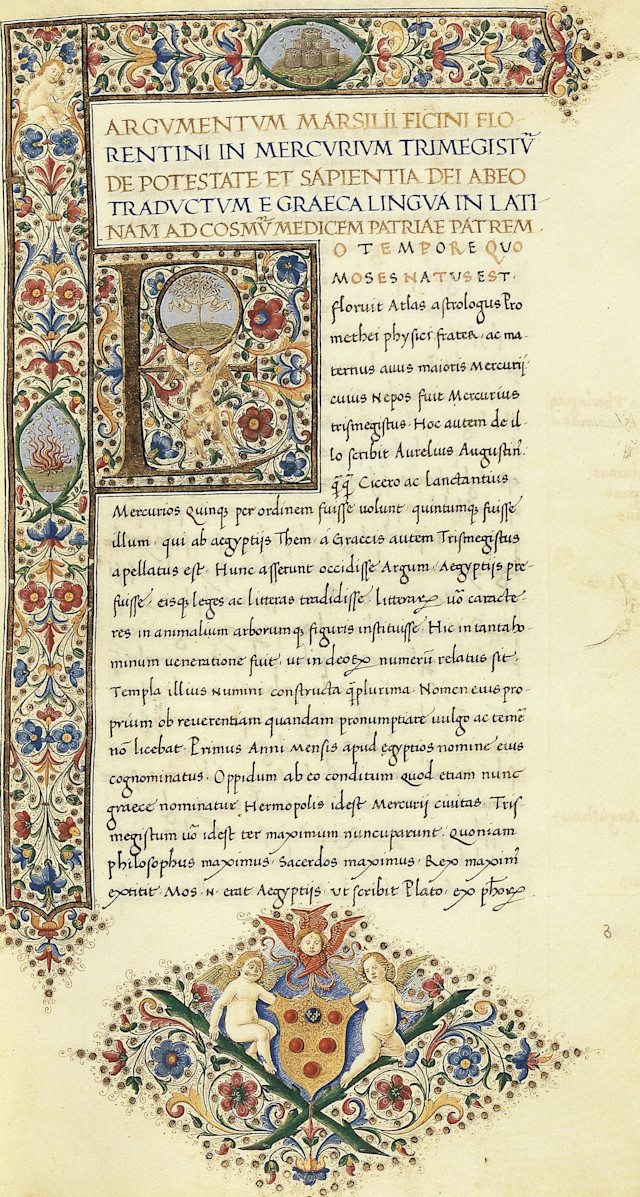

Pagans thinkers across most cultures believed in something that we might call the “science of idol-making”. Their understanding was that if you build a physical object in just the right way — such as a statue — and you performed certain magical rituals on it, you could actually lure and summon a spirit into the statue and bind it there. This is the same idea behind the “genie in a bottle” — a powerful spirit trapped in a physical object.

Marsilio Ficino’s 1491 Latin translation of the Corpus Hermeticum (source)

This was what pagans were doing when they built idols: they created statues of gods or spirits and lured or bound those spirits into them so that they could gain access to the spirits’ powers. You might think of this as pure superstition, but if you are a Christian, you should take it more seriously than that: the Biblical authors and the early Christians all believed in and took this practice very seriously — that’s why they condemned it.

What am I saying, therefore, about the advent of this new technology? I don’t want to say anything too strongly yet. I’m not saying that computers are “the devil” or anything like that. It’s just that when I hear that we are, in essence, working very hard to build physical objects in such a way that we can put a kind of “mind” inside of them that can predict the future or tell us what’s best — well, let’s just say it reminds me too much of things people used to do in the ancient world.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month