The short answer

Sexual fasting is a fast like any other fast: you abstain from sexual activity for some duration of time. The goal is to avoid being a slave to your sexual impulses, but instead to surrender them to the heart and mind thereby becoming more in harmony with yourself.

If you’ve been around traditional religion enough, you may have gotten the sense that “the church” is not a huge fan of pleasure. Restrictions on food, alcohol, or sex can give the distinct impression that Christianity is against pleasure or even happiness on the basis that those things are “worldly”. But this is a misunderstanding. In reality, it’s quite the opposite, and certainly not something unique to Christianity.

Abstaining from various pleasures or even voluntarily making your life harder is something common to all the major religious traditions. From the month-long Ramadan fast in Islam to the fasts on Uposatha days in Buddhism to dietary prohibitions among ancient Greek philosophers, there is a universal understanding across all cultures and time periods that fasting is an essential element in learning self-control. The name for this kind of practice is asceticism, a Greek word that originally referred to the rigorous training athletes put themselves through.

When you think about these kinds of fasts, you probably think of them mainly as concerned with abstaining from food and sometimes drink. However, it’s very common for many traditions to fast also from sexual acts. This might seem odd to a modern person, but if you think about it, you may see that it quite naturally goes along with the whole purpose of fasting.

Definition of abstinence: what is a sex fast?

Sexual fasting is a fast like any other fast: you abstain from sexual activity for the duration of your fast. Unlike fasting from food, however, a sexual fast is usually something you don’t do by yourself. If you’re married, it’s something you ought to discuss with your spouse, in the same way that if you were the person responsible for doing the cooking in your home, you wouldn’t decide to stop eating (and therefore cooking) and not discuss it with the other people in your house. In his letter to the Corinthians, St. Paul writes that spouses ought to agree together about sexual fasting, so that they’re both on the same page, and also that your time of abstinence be limited in order to not test your self-control beyond what you can handle (1 Cor 7:5). It’s more or less the same as other kinds of fasting. But to understand such fasts better, we need to put them in the context of the real purpose of fasting.

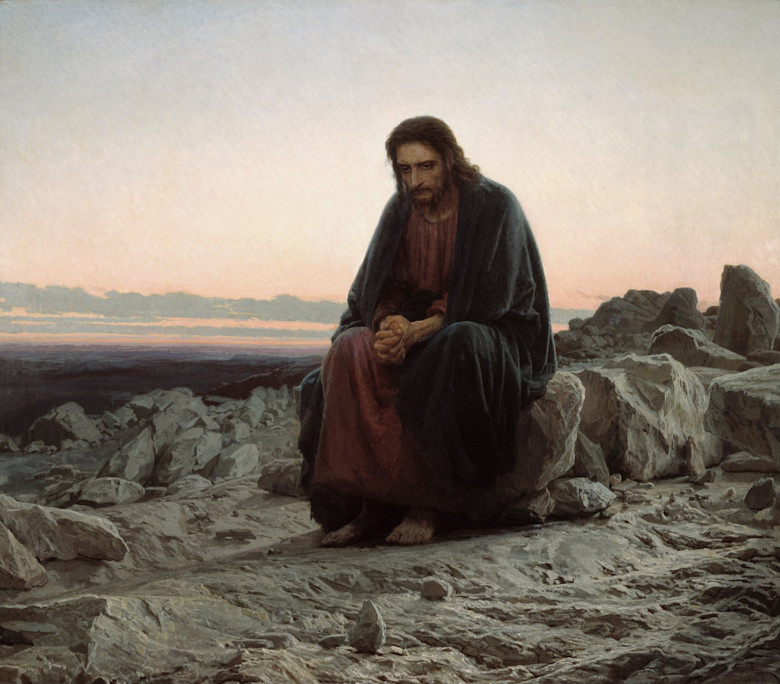

Christ fasting in the wilderness by Ivan Kramskoy - 1872

Fasting and the body

Depending on which religion you’re following, there will be important differences in how you understanding fasting. For many religions, fasting is a part of escaping or denying the needs of the body. This is because a lot of older or more eastern religions, like Buddhism, believe that the body is not really that important, and that what’s more important about you is the soul. In religions that believe in reincarnation, for example, the understanding is that your body is of such secondary importance that you can be reincarnated in any form – human or animal or even a god – but what endures across each body is the soul. Such religions use fasting as a way to separate the body from the soul, to focus more on your “true” self and get away from the distractions of the body – distractions like physical pleasure. In certain religions, the body is even seen as a prison for the soul, and fasting and asceticism are ways to escape from it.

Christ really had (and has) a body. Our bodies are therefore a good and important part of who we are.

How then do we understanding fasting on a Christian view of the body if asceticism is not about escaping the body? There are unfortunately many ways in which well-meaning Christians misunderstand the purpose of fasting because they misunderstand the role of the body. One mistake is to think that the body is somehow inherently evil or sinful, or that human beings have a “sin nature” that can’t help but do evil, and that this is somehow associated with the body. In other words, the body is still ”a problem” for many people even when they try to adopt a Christian view of it.

When my grandfather died I remember going to the burial hoping to have the opportunity to visit my grandmother’s grave, as she had died about nine years prior. However, when we arrived, all of the dirt from digging my grandfather’s new grave had been piled on top of my grandmother’s grave (as they were side-by-side). Standing around waiting for the proceedings, I mentioned my disappointment to my uncle. “I really wanted to see grandma,” I said, “but they piled all this dirt on her.”

My uncle replied, “Well, she’s not really here. She’s in heaven.” His idea was that, despite the obvious fact that her body was in the ground right next to us, “she” – that is, her real self – was not really present; “only” her body was here. This is the idea that you are a soul or a spirit, but that you merely have a body, and that the body is something you ultimately want to overcome or leave behind. People who believe this usually view fasting – even unconsciously – in a similar way to those religions that view the body as a problem: as a prison that you need to escape from or as a source of sin that you need to overcome. This confusion about the body leads to a confusion about fasting.

A Christian understanding of the body

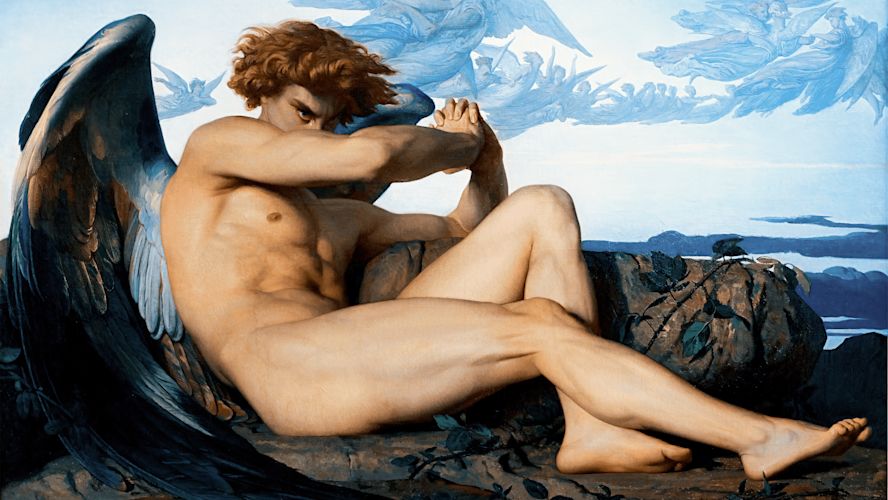

The devil tempts the hungry Christ with bread - Mosaic in Basilica di San Marco

(Ancient Christians referred to the “mind“ and ”soul” or “spirit” in interchangeable ways, different than how modern people think of them, where the soul was something like the highest faculty of the mind, the part that’s above the merely intellectual element of the mind – specifically, it’s the part of the mind from which you pray.)

If the human being is composed of three parts, how should those parts be organized? This is one of those timeless human questions, and the answer that’s been given by the greatest thinkers in Western history is that even though all three of these parts are equally important and equally you, not all of them have the same job, and they can’t (and shouldn’t) all be in charge of you. In order for the human being to be in harmony with itself, there has to be a hierarchy of these parts, namely, that the "lower" faculties (the body) need to be obedient to the "higher" faculties (the heart and mind). The early Christians did not disregard the body as something unimportant or evil – Christ truly had a body, after all – but they said that the body and its needs needed to be obedient to the other two parts. You might say that the body is the “youngest brother” among the mind and the heart.

This makes sense given the nature of the body. The body's needs tend to be intense, urgent, and short-sighted. When you’re thirsty, you want water. When you’re hungry, you want food. When you feel sexual urges, you want sex. The body doesn’t really ask questions like, “is it good for me to eat this particular thing at this particular time?” or “should I really be having sex with this person at this time?” because the body doesn’t really think – it just wants.

Naturally, if you always obeyed these impulses you’d live a very short-sighted life and probably get yourself into a lot of trouble. You certainly wouldn’t have much self-control. In fact, the early Christians recognized that if you always gratified your body’s desires, you wouldn’t be a free person – you’d be a complete slave to your impulses. Anyone with an addiction or bad habit knows that they actually have less freedom over their actions, not more.

Limitations on sex, including sexual fasting, are therefore also important

The goal, of course, is not to disregard or ignore the body, but to achieve self-mastery. The way you do this is by training your self-control through the temporary denial of the body’s impulses. This is the essence of sexual fasting, or any kind of fast. You don’t completely abandon food, drink, and sex – all of which are inherently good things. But you also don’t want to lose your self-control and become enslaved to your body. Those things simply need to be put in their proper place. Only then can you be in harmony with yourself and – in the language of the early Christians – become a more whole person.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month