What is the sin of envy in the Seven Deadly Sins?

The short answer

Envy is one of the major sins in Christianity. It is mostly about wanting what other people have, and while it’s often seen as being "discontent", the fact is envy is more often about resentment.

Some people think that envy as a sin is a silly idea. The idea that it’s wrong to see something you want and become motivated to get it is, in a certain sense, the entire basis for our economic framework in the modern West, and there’s a lot you could say about the value of positive motivation towards a goal.

What is the mortal sin of envy?

The deeper, more nefarious issue with envy is that it’s usually founded upon resentment.

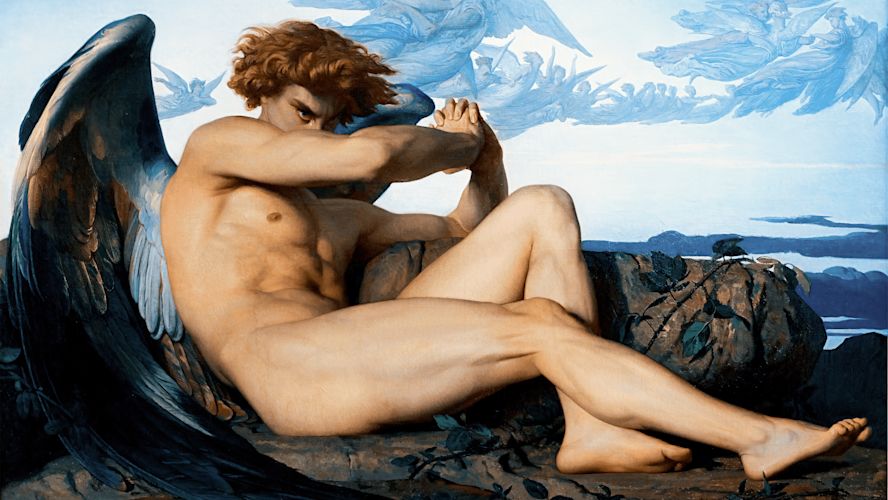

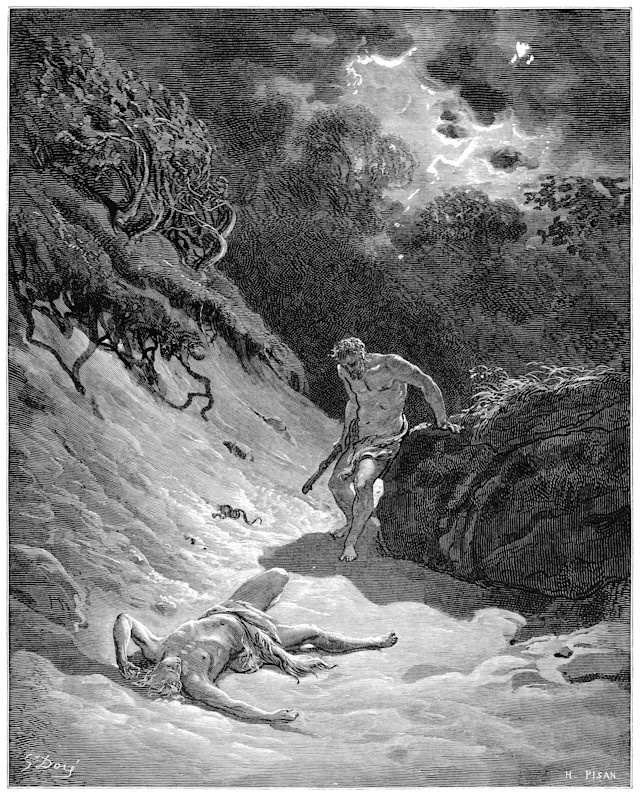

Cain slays Abel in this 1866 engraving by Gustave Dore

The impulse to hate and destroy that which you don’t have is the essence of the kind of dark resentment that hides at the base of envy. This comes up all the time in worldly issues, especially politics. It’s very common today to see movements and groups who claim to be disadvantaged in one way or another, but their requests for accommodation so often contain (and sometimes only barely disguised) the desire to destroy and tear down those things or groups that they view as responsible.

This is why we have to be very careful about how we look at our relationship to others. Being inspired to be better by someone else is of course a good thing; but ingratitude towards the good things in your life, let alone any amount of hatred, resentment, or desire for someone else to fail, is where this sort of thinking becomes sinful and self-destructive.

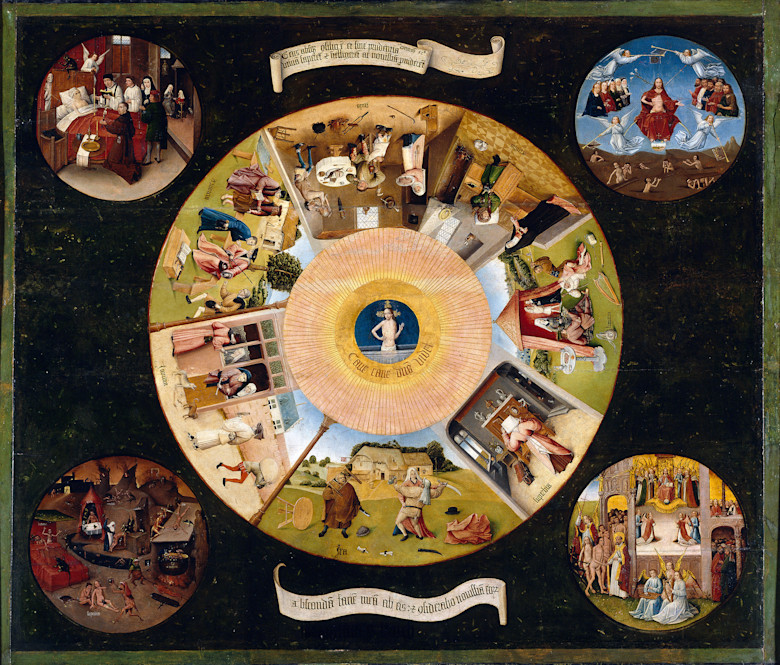

The Seven Deadly Sins and their meanings

Envy is listed as one of the Seven Deadly Sins, a popular list in Western Christianity since the Medieval era. What most people don’t know about this list is that the Seven Deadly Sins is only the most recent version of a list that has been re-shaped several times over the centuries. One interesting detail about this tradition is that envy isn’t one of the original “deadly” sins. Analyzing why that is gives us a better sense of what Envy really is, deep down.

The idea of keeping a distinctive list of sins goes all the way back to the early Christian Evagrius Ponticus in the fourth century. He composed a short explanation of these in his work On the Eight Vices, in which he categorized the major vices according to whether they were of the body, the heart (or emotions), or the mind. He listed Gluttony, Lust, and Avarice (or “greed”) as the three sins pertaining to the body; Dejection (or “sadness”), anger, and despondency (or ”listlessness”) for the emotions, and vainglory and pride for the mind.

Over time, however, this list of eight vices would become modified and condensed into the form in which we recognize it today. In the sixth century, Pope Gregory I revised the list: he combined dejection and despondency into sloth (or “laziness”); he combined vainglory and pride into just pride; and he added envy, bringing the total down to seven.

16th century painting of the Seven Deady Sins (in the middle) and the Four Last Things (in the corners)

Much, much later in the late Medieval period, Thomas Aquinas would base his own list of sins on Pope Gregory’s, which solidified them in Catholic tradition. They would be taken up by Lutheranism in the centuries to follow, and by that point this particular list of sins became the standard in the Western imagination.

Different lists of the Seven Deadly Sins

If you search around for different lists of sins, you’ll find many different variations. Which is the most authoritative list? It’s hard to pinpoint it exactly, as it depends on who you read. Part of the problem is that people use different words to describe the different sins, such as “avarice” for “greed”, “excess” for “lust”, and “listlessness” for “sloth”. It’s important to keep in mind that these variations are mostly due to translation. The original list of vices were written in Greek, and some change happened when they were translated into Latin, and then finally into English. Not all of them translate exactly into another language, and this has produced some of the changes in these lists over time.

There are also different kinds of lists that have appeared through the spiritual tradition of Christianity. The most notable alternative is probably from St. John Climacus’ The Ladder of Divine Ascent, in which he compiles a much longer list: avarice, anger, pride, gluttony, lust, fear, despondency, deceit, vainglory, malice, slander, talkativeness, and insensitivity. There has a been a lot of debate about the history and the evolution of these kinds of lists, even to the point where it’s been hypothesized that the “personality test” known as the Enneagram is actually a direct descent of this spiritual tradition in Christianity.

But what actually is sin?

However, what’s more practically important than establishing the exact, “definitive” list of which are the major sins, is how to think about sin in general. Part of why the idea of “sin” is a sore spot in the modern West is that many people feel judged by the idea of sins, and they feel condemned and therefore defensive about this topic. I think that’s the wrong way to think about sins. The problem is that Western tradition since the Medieval era conceived of sin primarily in terms of a punishment, and so part of the purpose of categorizing sins was to discern exactly how guilty you were for committing different of the sins (as in the distinction between “mortal” sins and “venial” sins). No wonder modern Western people are so anxious about this topic!

Early Christians understood sin, not as a crime, but as a disease.

The problem of sin as the early Christians understood it was as a disease that lead to death. The goal of religious life was to overcome sin, to become healthy so that you can ultimately be cured of death by participation in Christ’ conquering of death and evil.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month