Who were Jannes and Jambres in the Bible?

The short answer

Jannes and Jambres were the magician’s in Pharoah’s court in the Book of Exodus who Pharoah calls to show miraculous signs against Moses and Aaron, the leaders of the Israelites. The story shows the overwhelming power of the Christian God against the feeble power of lesser evil gods.

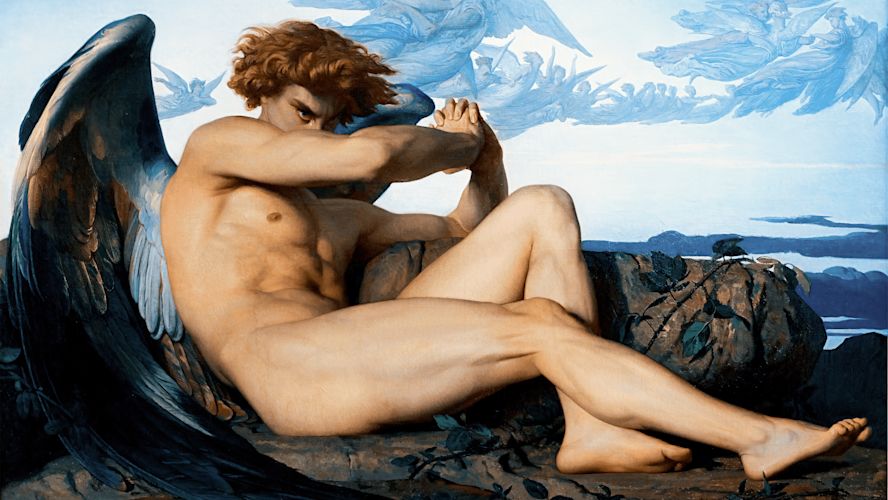

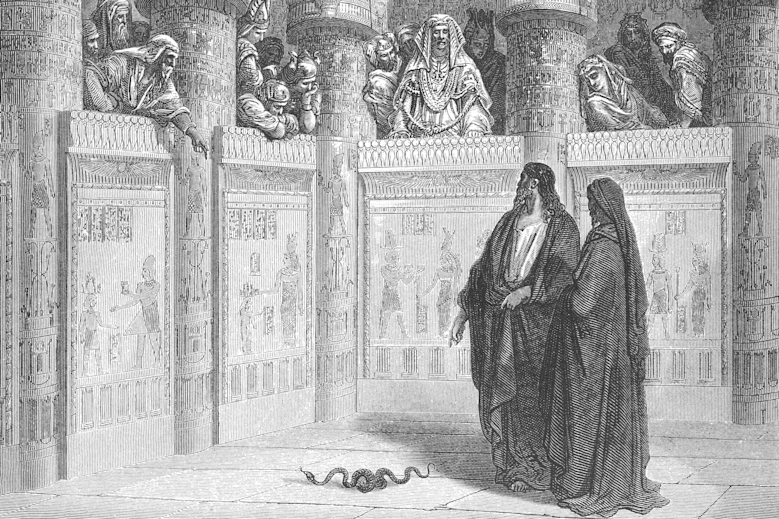

The 7th chapter in the Book of Exodus records something like a “wizard battle”. When Moses and Aaron appeared before Pharaoh, king of Egypt, he asked them to perform a “sign” or miracle in order to validate the truth of their claims about God sending them to free the Israelites. Aaron throws down his staff, which transforms into a snake. Presumably unimpressed by this, “Pharaoh called the wise men and sorcerers and magicians of Egypt, and they also did the same things by their magic arts. Each one threw down his staff, and it became a serpent. Yet one of them is clearly the victor. ”But Aaron’s staff swallowed up the other staffs” (Exodus 7:11-12). What do we make of this?

Moses and Aaron's snake devours Pharaoh's snake - Gustave Dore

While Aaron performed the miraculous sign by the power of God, apparently Pharaoh’s magicians could do the same thing by some other power. The main distinction doesn’t seem to be between ability (as they both could perform the sign), but degree of power: Aaron’s serpent eats the other serpents, showing that his God is greater than the gods of Egypt. Yet both of these acts appeared to be more or less the same.

That both sides in this conflict could produce the same miraculous effect prompted several ancient pagan writers, like Apuleius and Pliny, to include Moses in their lists of famous magicians in the ancient world, effectively grouping him in the same category as the sorcerers and magicians of Egypt – Moses was raised as an Egyptian, after all.

Pharaoh's magicians: Jannes and Jambres

There also appears to be an independent tradition about these figures, attributing the names “Jannes” and “Jambres” to some of those magicians who presided in Pharaoh’s court. In the New Testament – a record from centuries later – St. Timothy references these magicians by name, even though they aren’t named in the passage from Exodus: “Just as Jannes and Jambres opposed Moses, so also these men oppose the truth. They are depraved in mind and disqualified from the faith” (2 Tim 3:8). The early Christian writer Origen claimed that this tradition was preserved in an apocryphal book called The Book of Jannes and Jambres, which he believed Timothy was quoting from. Since that book has not been rediscovered by modern scholars, we can’t verify its contents, but it makes sense that St. Timothy would have inherited that knowledge from some older tradition.

Rod of Aaron turned into a serpent - Phillip Medhurst

So, were Moses and Aaron “magicians”? How did Pharaoh’s magicians have access to such abilities if they really “opposed the truth” in opposing Moses and Aaron? This gets us at a question that modern people often struggle with: the definition of “magic”.

What is magic and magicians in the Bible?

Modern people have a hard time with this question because, by default, we only believe in the physical world. We believe that things are “just” things: emotions are “just” chemical reactions, water is ”just“ a liquid, writing is “just” marks with ink on paper, and so on. We see the world mostly as a collection of objects that obey blind, physical laws. If you’re an atheist or skeptic of some kind, then you believe that that’s really all there is in the world. If you’re a religious or “spiritual” person then you believe the same basic thing, you just believe in “extras”. Extras could be anything – the soul, karma, God, spirits, or miracles. Basically anything we would call “spiritual”. It depends on your beliefs, and modern people have a wide range of different beliefs about those things. But the thing almost all modern people have in common is that they believe in the physical world of natural laws as the primary world, and everything else as an addition, as something “supernatural”. The philosopher David Hume is a good example of this belief: he famously defined a miracle as a “violation” or “exception” to the laws of physicals. In other words, the laws of physics are normal, and supernatural things are exceptions.

Even many modern Christians believe something like this, such as the idea that the world normally obeys the natural laws of physics, but that God can suspend them whenever he wants to. When you think about the world in this way, it becomes difficult to distinguish between “magic” and a “miracle”; they effectively look the same. “Magical” even becomes a kind of synonym for “false” or “unreal”. A “magic trick” is, after all, an illusion. Everyone “knows” that magic isn’t real – though a modern Christian may add that God can do real miracles – but only as an exception.

This was not a view held by pre-modern or ancient people, including the early Christians. Ancient people didn’t believe that there were two “levels” to reality: the natural and the supernatural. They believed that there was only one level to reality, and that the physical and the spiritual were fundamentally interrelated in everything. This means that everything physical has a spiritual component to it, and that (almost) everything spiritual has a physical manifestation to it. This is why all ancient cultures, in every religion, use physical things – incense, altars, sacrifices, sacred images – in their worship.

Ancient people didn’t believe in things like “laws of physics” in the same way that we do today. They didn’t believe that the universe was a collection of objects functioning according to arbitrary laws and forces, they believed that the world was full of minds – humans, spirits, gods – and that interacting with any part of the universe always, therefore, included an element of personal relationship. Yes, the sea had a nature to it, but almost more fundamental than that, the sea obeyed the god of the sea, so if you had a good relationship to that god, the sea might behave differently for you. Famously, Odysseus did not have the blessing of the god of the sea, quite the opposite, which was part of the main problem in the story of the Odyssey.

Modern people tend to view this sort of thing as superstitious and even silly, but there’s a real sense in which this way of looking at the world isn’t really any more arbitrary than a modern, scientific way. If you think about it, the way that we view something like the law of gravity is very abstract and mysterious: gravity is something that exists, there’s no real explanation for it. The scientific explanation is that there isn’t something more fundamental that causes gravity to work the way it does, it just does. Gravity just “is” – that’s all.

But another important point is that even from a scientific perspective, it’s not really possible to dimiss this personal element. Studies in quantum physics and the placebo effect have given us very good reasons to think that our minds actually influence how the physical world works, which very strongly suggests that there really isn’t that much of a gap between the two as you might be led to believe.

The ancients, therefore, didn’t group all “supernatural” phenomena in the same category. They thought, in a real sense, that the whole universe was enchanted and full of meaning. Jesus’ twelve closest disciples, for example, rolled dice (“cast lots”) to determine who should take Judas’ place in their group of twelve after he killed himself, because they didn’t believe that physical things were merely “random chance” but had real meaning to them. The idea that people could cause the natural world to behave in various ways and through various methods was a universally accepted practice, though they understood it in different ways.

Some, like the pagan thinker Plotinus, believed in what he called “sympatheia”. This is the idea that because everything in the universe is connected at some level, things that are similar to one another can attract or affect one another. You might call this a kind of “natural magic”. It appears in basically every culture, including modern new-age movements.

The other major phenomenon is the interaction with spiritual creatures. If you invoke – or sometimes coerce – a spiritual entity that has power over some part of the physical world, then you can get it to alter the world for you in some way. If you can placate the god of the sea, maybe he’ll grant you safe passage through a storm. This kind of relationship wasn’t always cooperative, sometimes it was coercive: if you trap a spirit you can, essentially, enslave it to do your bidding. That’s where the legend of a genie in a bottle comes from. Interacting with these spirits, because they were fallen and corrupted by their evil desires was a dangerous business. This explains the Bible’s frequent admonitions to the ancient Israelites against engaging with the magical practices related to the worship of those gods (Zech 10:2, Isai 8:19-20, 2 Chron 33:6, Deut 18:9-12).

But of course, the most important spiritual entity is the God of all the other gods, the lord of the hosts of heaven. While all the spiritual entities of the ancient world are presented as having some amount of power over the natural world – from Homer to the Bible – when it comes to a contest between the lesser gods and the God of gods, the God of the ancient Israelites and the early Christians, there is no contest. The God of ancient Israel is called the “God of gods” to indicate the degree of this difference. The regular gods – Zeus and Thor and such – are almost infinitely more powerful than us mortal humans. But what if they had a God? That God would have to be infinitely greater than them. And this is how early Christians described the “Most high God”: he is beginningless, timeless, ageless, spaceless, the source of all life and being. There are none like him among all the gods (Psalm 86:8).

This is why even though both sides can turn staves into serpents, Aaron’s serpent devours the others. When God sends the various plagues on Egypt, Pharaoh’s magicians can keep up with them at first – because they do have some real power, presumably through the gods of Egypt – but ultimately they are defeated. What else would you expect?

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month