Healing is the children's bread?

The short story

The phrase “healing is the children’s bread” does not exist in the bible. What does exist in Matthew 15 is a story about how bread and healing is less important than humbling ourselves before God.

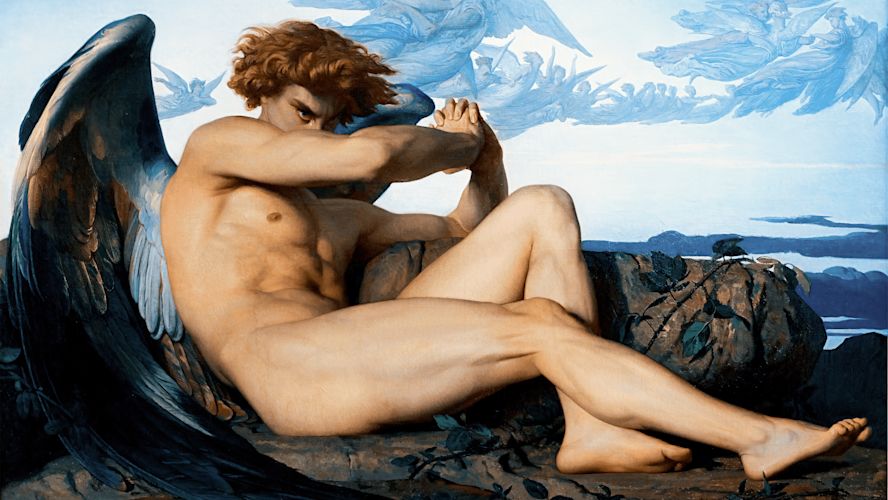

The pop-culture image of Jesus is that he was a “nice guy”. He was compassionate and gentle with everyone and certainly didn’t deliberately put people down or antagonize them. Or did he? There is a fascinating passage in the Gospel of Matthew where a woman asks Jesus for healing, and Jesus not only initially denies this request but enters into a back-and-forth dialogue with her, repeatedly brushing her off and going so far as to compare her to a dog. It’s certainly not your typical image of “nice-guy” Jesus.

Juan de Flandes - Christ and the Canaanite Woman (circa 1500)

Is healing really the point?

There are many ways to interpret this passage, but the kind of modern commentary that’s easy to find on the internet tends to focus on healing as the central issue. Namely, the “bread” she is asking for is healing, healing that properly belongs to the children of Israel, but which the woman asks to have for herself as well. Modern commentators tend to see this passage as a guide for how to receive healing from Jesus, as if Jesus is testing you and you need to say things in just the right way to get healing from Him. Others will say that healing is something that “belongs to you” as a child of God, and that’s why the woman is so persistent, as though she “knew her rights” and insisted on them when God tested her. I’ve even heard someone go so far as to say that “healing is a basic right of every child of God”.

Reading the passage this way invites a strange way of looking at Jesus. It makes Jesus sound like he’s testing or provoking the woman, or that he’s only going to give her what she wants if she says or does the right thing, which sounds a little cruel in the context of someone coming to him in desperation and need. Is there a different way to read this passage?

Humility is what heals

Thinking of healing as a “right” or something you “deserve” from God doesn’t line up with the spirit of humility that is presented again and again in the New Testament. You’ll notice that Jesus never says anything about rights, still less to insist on what he (or anyone else) owes you. In fact, he says the exact opposite.

Let the Little Children Come unto Jesus - oil on copper by Carl Bloch (circa 1800s)

Nowhere do we see Christ calling us to insist on what is owed to us or demand from God what we feel we deserve. To the contrary, Jesus frequently reminds us that the way to achieve greatness is – paradoxically – through humility. Jesus points this out later in Luke’s account, when he explains that “Whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and he who humbles himself will be exalted” (Luke 14:11). Because the early church fathers understood this idea, they read this episode with the gentile woman as fundamentally about the woman’s humility.

The interpretation of the church fathers

St. John Chrysostom, one of the greatest Biblical commentators of late antiquity, reads this passage in a completely different light than the modern “prosperity” reading. St. John sees Jesus’ interaction with the woman, not as a challenge, but as his way of revealing her great virtue. He writes:

"He would not that so great virtue in the woman should be hid” (in other words, he doesn't wish for her virtue to be hidden), and it is ”not in insult then were His words spoken, but calling her forth, and revealing the treasure laid up in her."

St. John Chrysostom - Homilies on the Gospel of Matthew, Homily LII, 3

In other words, Christ is not insulting the woman or even testing her, but is “calling her forth” to reveal the treasures inside of her. He arguably does this for the benefit of his disciples, who, instead of having sympathy on the woman, tell Jesus, “Send her away, for she cries out after us” (Matt 15:22). They say this when Jesus initially says nothing in response to the woman’s request, which makes more sense if we understand that he is trying to get her to reveal herself.

What is this treasure that he is trying to get her to reveal? It is her humility. St. John sees the woman’s reply not as an insistence on her rights, but a humble acceptance of her position. She doesn’t argue with Jesus, but accepts being called a dog, and precisely on the basis of being a dog, argues that she is not in fact forbidden from partaking of Christ’s healing. St. John rewrites the woman’s reply in his own words to bring out this point:

“Yet neither am I forbidden, being a dog. For were it unlawful to receive, neither would it be lawful to partake of the crumbs; but if, though in scanty measure, they ought to be partakers, neither am I forbidden, though I be a dog; nay, rather on this ground am I most surely a partaker, if I am a dog.”

St. John Chrysostom - Homilies on the Gospel of Matthew, Homily LII, 3

This dynamic is totally different: it’s not that Jesus is calling her a dog and she’s insisting that she isn’t, he’s pointing out that as a Gentile she is second to the children of Israel, but she accepts this entirely because she is humble.

Illustration of Origen of Alexandria from Schäftlarn manuscript (circa 1160 AD)

But, according to Origen, it is precisely because the woman acknowledges this hierarchy and accepts her place in humility at the bottom that she receives her reward. He writes:

“But when she, with intensified resolution, accepting the saying of Jesus, puts forth the claim to obtain crumbs even as a little dog, and acknowledges that the masters are of a nobler race, then she gets a second answer, which bears testimony to her faith as great, and a promise that it shall be done unto her as she wills."

Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, Book XI, 17

St. John points out that Jesus doesn’t merely say, “great is your faith, your daughter is healed”, but he tells her, “Let it be to you as you desire” (Matt 15:28; emphasis mine). In other words, he doesn’t simply grant her request; he finds that she is so full of the right spirit of humility that he grants her whatever she desires.

“For to this purpose neither did Christ say, ‘let thy little daughter be made whole,’ but, ‘great is thy faith, be it unto thee even as thou wilt;’ to teach thee that the words were not used at random, nor were they flattering words, but great was the power of her faith.”

St. John Chrysostom, Homilies on the Gospel of Matthew, Homily LII, 3

The temptation to interpret this passage as an insistence on your rights is, therefore, the opposite of how the early Christians interpreted it. It makes Jesus sound picky and harsh, and the woman sound proud or entitled, when the reality is that her virtue is humility. Jesus, knowing this, puts her in a situation where she can display that humility – perhaps to teach his disciples yet another lesson about what it really means to be great.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month