The short answer

It’s not very clear when exactly Jesus was born, as the Gospel accounts don’t specify it, nor are there other historical accounts that might help. Different dates have been proposed. But despite the lack of consensus, it’s still correct to celebrate Jesus’ birth according to the traditional date.

Everyone knows that Christmas is in December, but was December actually the month of Christ’s birth? The gospel accounts don’t say, nor does anywhere else in the New Testament give an exact date. How should we take this?

The first thing you have to understand about this is that there was no real universal standard of keeping time in the ancient world. Every culture had its own calendar: some had solar calendars, some had lunar calendars, some had 10 months, others had 13.

The Roman calendar—which would have been something like a standard for the ancient world during the time of Jesus’ birth—was famously flexible. The Roman calendar only had 355 days, so it would quickly become out of sync with the actual seasons of the year. The Roman solution was to insert an extra month into some years between February and March called the intercalary month, which was a variable amount of days, depending on how many days they needed to reconcile the calendar year with the seasons. There were a variety of shenanigans associated with this sort of calendar adjustment process, where the official in charge of making the adjustment might lengthen the years during which his political allies were in office and shorten those years in which his political enemies were in office!

These sorts of inconsistencies is why it’s difficult to date any ancient sources exactly, not just the birth of Christ. However, I think it’s important to point out that the greatest efforts towards standardizing the calendar were begun in Rome but completed by the Church. The Churc ultimately established the calendar that the whole world uses today.

I always find it weird that people are so skeptical towards Christian dates like the birth of Christ on the basis that these are “theologically” motivated, as though such motivation invalidated the qualifications of the people doing those calculations. In fact, Christians were some of the best mathematicians and astronomers of the ancient and medieval world — they were certainly some of the most devoted copiers of manuscripts and preservers of literacy. It is because of much of their record keeping that we’re able to date many of the events of the ancient world with accuracy — for example, because they kept such thorough records of the lines of succession of bishops from the original apostles. This succession of bishops was undoubtedly a helpful, independent dating system in a world where years were often based on the succession of temporal rulers—such as the emperors.

What year was Jesus born?

Nativity with a Torch by the Le Nain brothers, c. 1635-40

What month was Jesus born?

Ancient sources are much more confident about the month and day that Jesus was born, generally agreeing that the date was December 25th. We have writings from such prominent figures of the early Church as St. Euodias of Antioch in the first century, St. Theophilus of Caesarea in the second century, and St. Jerome and St. John Chrysostom in the fourth century — all agreeing on the date December 25th.

There have been a few modern movements to demonstrate that Jesus’ birth was in September.

The various events prior to the birth of Jesus, as presented in the gospel accounts, have been used to help pinpoint the date. Luke’s gospel account begins with a lengthy description of an important event that happened before Jesus’ birth, namely, the conception of John the Baptist (Luke 1:5-23). He describes the Prophet Zacharias having a vision in the temple during one of the high holy days, which was likely Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. But this date itself is tricky, as Biblical scholars have used it both to prove that Jesus’ birth would in fact be December 25th, while others have used it to show that it would have been a date in September.

While there are a good handful of arguments for a September date, I think it’s significant that all of the revisionist dates have been proposed within the last few hundred years. All of the major sources in the ancient world, those within a few hundreds years of Christ’s life, proposed the December date. Does that mean an end to the discussion?

When is Jesus’ real birthday?

There’s a great deal of calculation, argumentation, and debate that could go into this topic, but I think that all of that is largely a distraction because this discussion is rarely, in my experience, about a sort of objective, neutral dedication to fact-finding and almost always has an ulterior motive. If you can demonstrate that Jesus’ birthday wasn’t actually December 25th, then it puts the Church and the early Christians in a bad light, implying that they were (at worst) knowingly subverting or corrupting the facts to suit their narrative, or (at best) mistaken.

The kinds of arguments people raise on these grounds, however, tend to show a lack of familiarity with the mindset of early Christians and the ancient world in general. Let’s look at one of the most prominent arguments against Christianity.

One thing that people tend to claim is that the Christians purposely put their feast days on the same days as pagan feasts — like the various feasts of the gods or the equinox, solstice, etc., to try and “subvert” pagan festivals. The feast of the Invincible Sun — sol invictus — was famously celebrated on December 25th, which is why some people argue that the Christians were intentionally “stealing” a pagan holiday, as though Christianity was entirely unoriginal and simply stole all of its symbolism from paganism. But when you actually read the writings of the early Church, you get a very different story.

They might argue December 25th was always originally going to be Christ’s birthday, but it was usurped by a fallen religion. Christians were simply taking it back.

It depends on how you look at the world. If you already come into the discussion with the prejudice that Christianity — and paganism — is false, then you’ll be more predisposed to believing that the pagan festivals are merely things people made up, and the Christian appropriation of them is just another thing people made up. But if you really believe in the spiritual world, then the true nature of the gods and their relationship to sacred times and seasons of the year is going to have real significance. Christianity’s narrative about the origin of paganism is going to make a lot of sense about why everyone believed in these pagan religions despite them being so often unpleasant. If the gods were real but fallen, that makes a lot of sense.

Understanding the liturgical calendar

The last thing I want to address is the issue of how to think about time. These discussions about dating systems generally miss the point, not because they aren’t important, but because this over-emphasis on the physical world only (the exact calendar calculations at the expense of spiritual content) would have been entirely foreign to the early Church (and to ancient people in general).

Christians (and pagans, for that matter) always understood that the physical world and the spiritual world are not separable. The idea of separating the two (and of making one “less” important or subjective and the other one objective and therefore more important) is simply a modern bias that would have totally confused the ancient Christians. Almost the opposite, in fact: the early Church believed that the physical world, while real and good, was only a shadow of the real world, of “reality itself” — something that was coming but had not yet arrived. They participated in this spiritual reality through the Divine Liturgy, the continuation of the temple worship of the ancient Israelites. The idea was that God had showed Moses how to participate in this spiritual reality through imitation, and in doing so, the worshipers would be caught up into the higher spiritual reality of the liturgy.

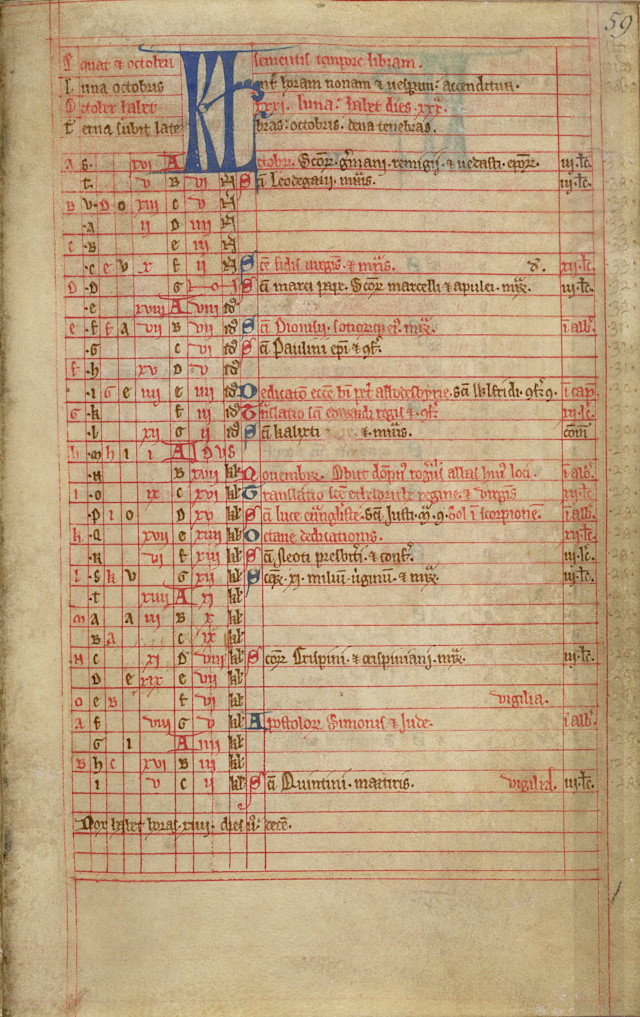

Liturgical calendar from a 13th century manuscript

The earthly calendar, with all its calculations and efforts to maintain accuracy, is not really the highest reality. We think it is because we have a bias towards that which is measurable and verifiable. But if this life is only a shadow of the age to come, and we participate in that higher spiritual reality through the power of liturgical time, then the liturgical calendar is not merely a reenactment of past historical events, but the organization of all these historical events into a cosmic structure that we can participate in, not as mere symbolism that’s secondary and therefore lower than normal, secular time, but as the true call to a higher spiritual reality that is in fact higher and more real than our mere earthly calculations. Celebrating Christmas on December 25th, because it’s part of liturgical time, is, in a Christian understanding, the more real date — in relational to all the other cosmic events of the rest of the liturgical calendar and therefore as a reflection of the true, cosmic time of the age to come.

Subscribe

Life-giving writing by Christian scholars sent to your inbox once per month